What is a Levy?

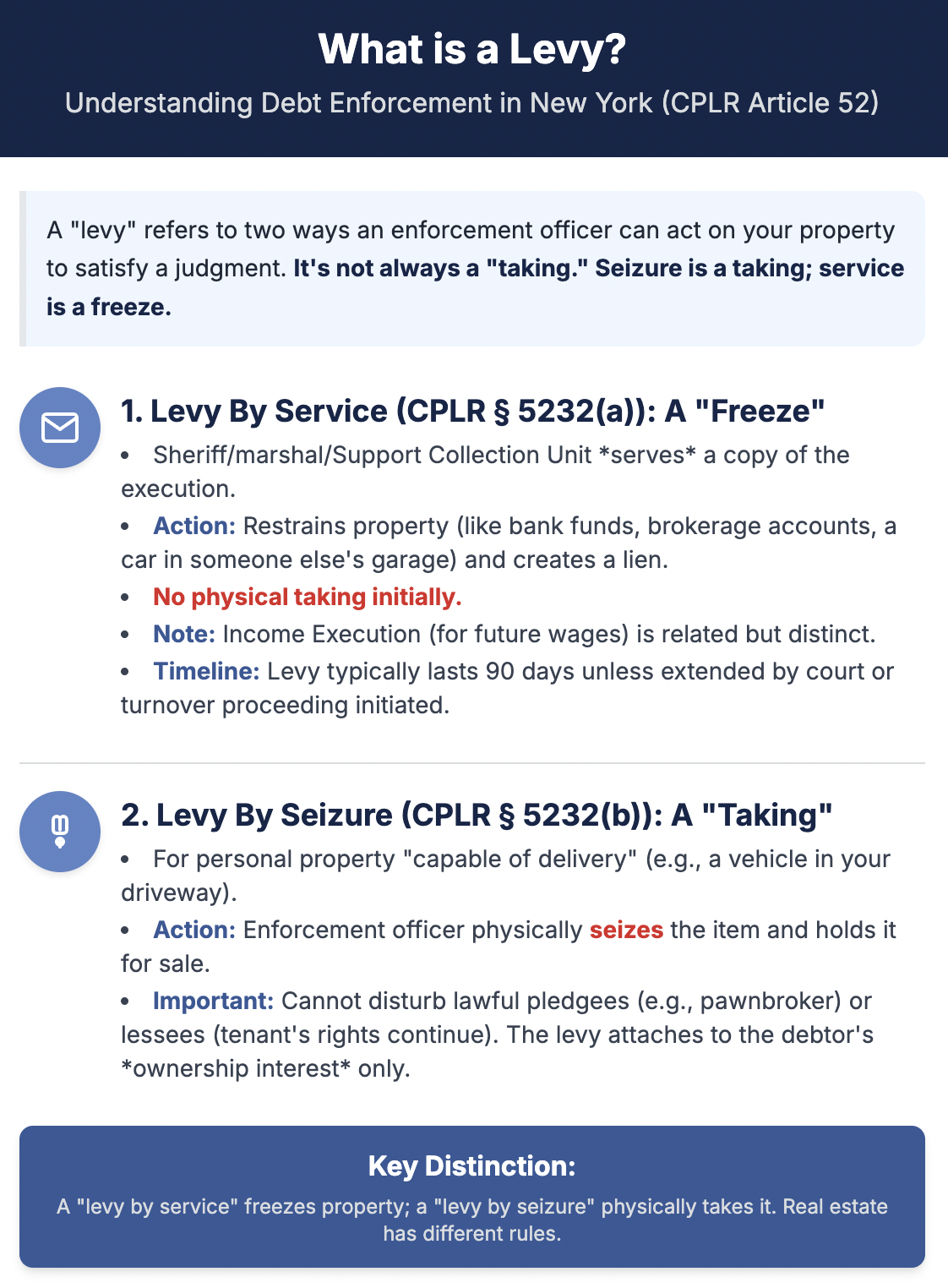

Under New York Civil Practice Law and Rules (CPLR) Article 52, the term levy describes two distinct enforcement methods:

Levy by service of execution (CPLR § 5232 (a)) – The sheriff, marshal, or Support Collection Unit serves a copy of the execution on the debtor or a garnishee. Service restrains the property and creates a lien; nothing is physically taken unless the property is later turned over voluntarily or through a turnover proceeding.

Levy by seizure (CPLR § 5232 (b)) – For personal property “capable of delivery,” the enforcement officer may physically seize the item and hold it pending sale.

A levy is therefore not always a “taking.” Seizure is the taking; service is a freeze.

The procedures below summarize New York statutory law (CPLR § 5232) for personal property only. Real estate is enforced under CPLR §§ 5235–5236 and follows different rules.

1. Levy By Service of Execution (for property that isn't "capable of delivery" like your future wages or bank funds)

1. Levy By Service of Execution (for property that isn't "capable of delivery" like your future wages or bank funds)

A designated sheriff, marshal, or support collection unit serves the execution in the same manner as a summons. The levy is effective only if, at the moment of service, the garnishee:

owes the debt,

is in possession or custody of the property, and

knows the property belongs to the debtor.

Examples include a debtor‑owned automobile in someone else’s garage, a brokerage account, or equipment on lease.

Income Execution vs. Levy

Future wages are collected through an Income Execution (CPLR § 5231), which has its own notice and percentage‑withholding scheme. It is related to—but not the same as—a levy under § 5232.

Waiting period / 90‑day life of levy. Until the property is turned over, or 90 days elapse, the garnishee may not sell, assign, or transfer the asset except to the enforcement officer. After 90 days the lien expires unless the creditor starts a turnover proceeding (§§ 5225 or 5227) or obtains a court extension.

Wrongful levies can expose judgment creditors and support collection units to damages.

Here is a summary of the common "Income Execution" that acts to levy against your wages. You may have received a Notice of Garnishment from a Marshal (i.e., Marshal Bienstock, Daly, Moses, or Biegel) or Sheriff threatening a wage garnishment.

2. Levy By Seizure

When the item can be physically delivered (e.g., a vehicle parked in the debtor’s driveway), the sheriff, marshal, or support collection unit may seize it without disturbing lawful pledgees or lessees, then hold it pending sale pursuant to CPLR § 5233.

NYC marshals ordinarily schedule a sale within about 60 days under administrative rules, but no statewide statute imposes a fixed sale deadline.

Pledgees – A pledgee is a secured creditor who already has the item in its possession as collateral (think of a pawnbroker or a bank holding negotiable instruments in a lock-box). The statute says the sheriff may levy “without disturbing lawful pledgees,” so the officer cannot simply grab the collateral out of the pledgee’s hands. Instead, the levy creates a lien subject to the pledgee’s prior security interest. The pledgee keeps possession; if the debtor defaults, the pledgee’s rights are paid off first from any sale proceeds.

Lessees – If the debtor has leased the property to someone else (e.g., a car leased to a third party or equipment on a long-term rental), that lessee’s right to use the property continues. The enforcement officer cannot evict the lessee or interrupt the lease merely because of the levy. Again, the levy attaches to the debtor’s ownership interest subject to the lessee’s lawful right of possession.

Bottom line: the sheriff can impose the levy and ultimately sell the debtor’s ownership interest, but only as encumbered by whichever superior possessory or security rights were already in place. That protects innocent third parties and avoids exposing the sheriff or creditor to conversion and breach-of-peace claims.

3. Required Notices (Notice to Judgment Debtor or Obligor)

If the debtor has not received an EIPA notice within the previous 12 months, the enforcement officer must, within four (4) days of serving the execution, send a copy of the notice by personal delivery or first‑class mail. The envelope must be marked “personal and confidential” and must not reveal the sender’s identity.

A notice sent by mail must be sent to the debtor's residence. However, if returned as undeliverable or that address is unknown, then the notice should be sent to the debtor's place of employment, marked "personal and confidential," and not reveal from whom the notice was sent.

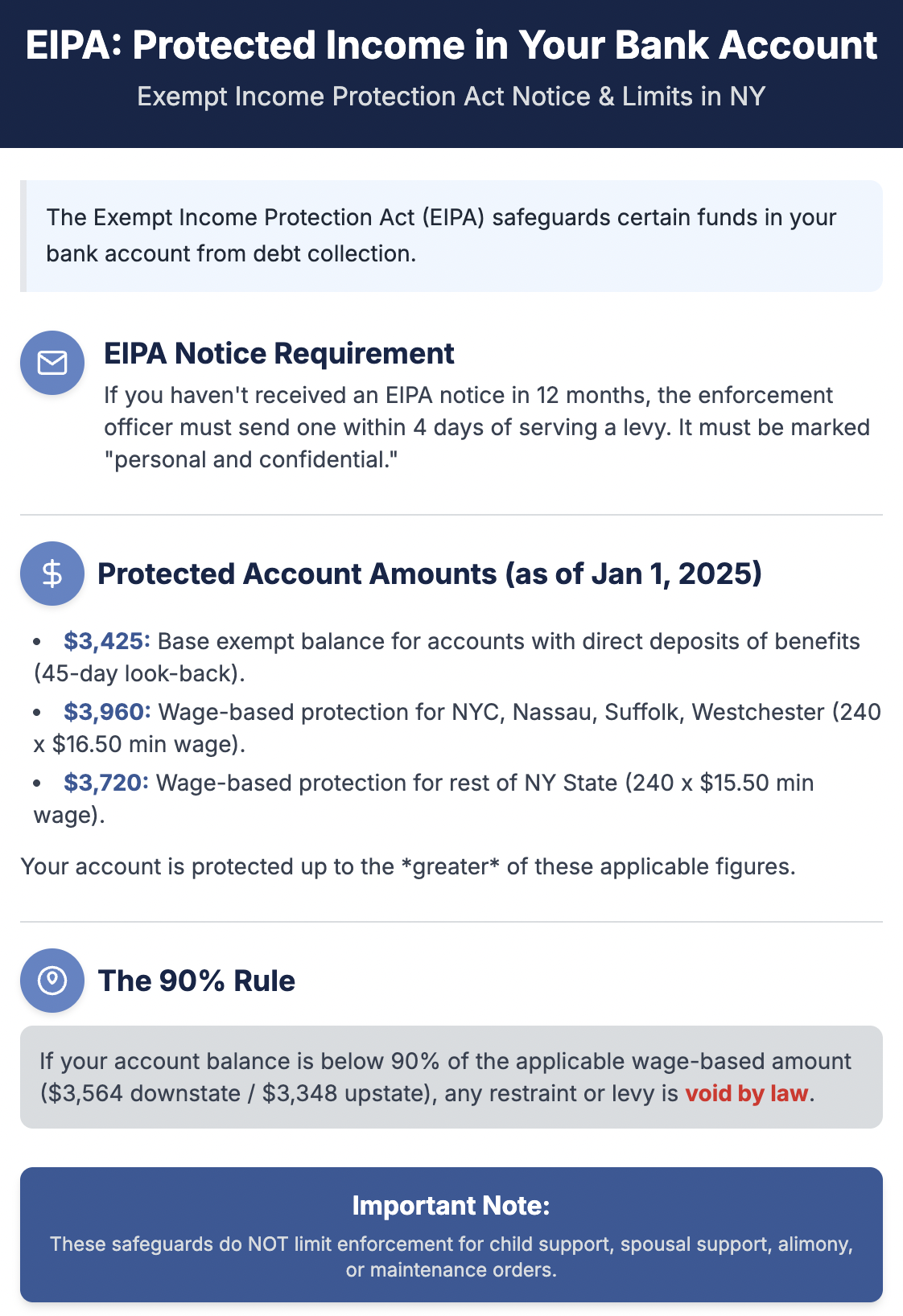

4. EIPA (Exempt Income Protection Act) Notice and Bank‑& Wage‑Account Protections

If the debtor has not received an EIPA notice within the previous 12 months, the enforcement officer must, within four (4) days of serving the execution, send a copy of the notice by personal delivery or first‑class mail. The envelope must be marked “personal and confidential” and may not reveal the sender’s identity.

Protected account amounts (current as of January 1 2025)

• $3,425 – Base exempt balance when the account received qualifying direct deposits of benefits during the 45‑day look‑back period (effective 4 Apr 2024; next CPI update Apr. 1, 2027).

• $3,960 – Wage‑based protected balance for debtors paid in New York City, Nassau, Suffolk or Westchester counties (240 × $16.50 minimum wage).

• $3,720 – Wage‑based protected balance for debtors paid elsewhere in New York State (240 × $15.50 minimum wage).

• 90 % rule: If the account balance is below 90 % of the applicable wage‑based amount ($3,564 downstate / $3,348 upstate), any restraint or levy is void by operation of law.

The account is protected up to whichever of these figures is greater. These safeguards do not limit enforcement for child support, spousal support, alimony, or maintenance orders.

5. Fees

Banks may not charge a fee for refusing to honor an execution because protected funds are present. Sheriffs and support units must serve EIPA exemption notices with the execution. Banks must hold restrained funds for 27 days and wait 30 days for exemption claims before releasing them. Fee exceptions apply when the judgment creditor is the State of New York or when the debt is for child or spousal support and the execution is properly labeled.

New York Law: Levies v. Seizures-Required Notices & Protections

| What the rule covers | Legal source | Link to Source |

|---|---|---|

Freeze vs. seizure distinction; 90‑day life of a service levy; need for a § 5225/§ 5227 turnover to keep it alive | CPLR § 5232 (a) | NY CPLR § 5232 (Justia) |

Levy‑by‑seizure language (when the officer actually takes the property) | CPLR § 5232 (b) | NY CPLR § 5232 (Justia) |

Four‑day notice to the debtor (only if no EIPA notice in the past year) | CPLR § 5232 (c) | NY CPLR § 5232 (Justia) |

| Bank‑account safe amount: $3,425 (effective 4 Apr 2024) | DFS industry guidance on EIPA CPI adjustment | DFS – Amount Exempt From Judgments |

240 × highest NY minimum wage multiplier (gives $3,960 downstate / $3,720 upstate for 2025) | DFS press release interpreting EIPA; CPLR § 5222‑i | DFS Minimum‑Wage EIPA Guidance |

| 27‑day / 30‑day bank holding period + exemption‑form service | CPLR § 5232 (g) | NY CPLR § 5232 (Justia) |

Income execution (wage‑garnishment device) | CPLR § 5231 | NY CPLR § 5231 (NYS Senate) |

| Levy and sale of real estate | CPLR §§ 5235–5236 | NY CPLR § 5235 (Justia) / NY CPLR § 5236 (Justia) |

| 60‑day sale timeline for NYC‑marshal seizures (administrative rule) | NYC Marshal Handbook of Regulations § II‑4‑2 | NYC Marshals Handbook PDF |

Frequently Asked Questions: Judgment Debtors’ Obligations (CPLR § 5232)

The questions below cover the most common worries people have once they learn a levy has been started against their personal property.

Q 1. What exactly can the sheriff “freeze” without touching it?

Any non‑exempt personal property that sits in someone else’s hands—your bank, broker, employer, renter, or anyone who owes you money. The sheriff serves that third party (the garnishee) with an execution, which instantly restrains the asset. You don’t have to do anything at that moment, but the garnishee must hold the property and later pay or deliver it to the sheriff.

Q 2. When does the sheriff actually take stuff away?

If an item is “capable of delivery”—a car, jewelry, inventory—the sheriff can perform a levy by seizure. The officer must hand a copy of the execution to whoever has the item, then physically remove it and store it for auction.

Q 3. Will I get personal notice a freeze or seizure?

Yes. If you haven’t received an EIPA notice within the last 12 months, the sheriff must mail or hand‑deliver a new notice within four days after serving the garnishee. The envelope will be marked “personal and confidential” and won’t mention debt collection on the outside.

Q 4. What if I ignore the levy notice regarding exempt assets in New York?

The levy moves forward anyway. The garnishee will have to turn over or pay the restrained property, and the sheriff can sell seized items. You also risk added legal fees or contempt penalties if you actively interfere.

Q 5. Does cooperating help me, and whom do I actually negotiate with?

Yes—provided you talk to the judgment creditor (or the creditor’s lawyer or collection agency), not the sheriff or marshal. The enforcement officer’s role is purely ministerial: serve papers, restrain assets, or seize property when the creditor instructs. If you and the creditor hammer out a written payment plan or settlement stipulation, the creditor can (and usually will) issue written instructions telling the sheriff to suspend or release the levy. That spares you a forced sale and saves the creditor auction costs, so many creditors agree as long as the plan is realistic and documented.

Q 6. How do exemptions work in New York?

New York shields some income and property: benefit deposits, a base bank balance, and tools of your trade, among others. File an exemption claim form within the deadline on the notice and the bank or garnishee must release protected funds.

Q 7. What if I send the exemption form too late (in New York)?

Late means you mailed or delivered the form more than twenty (20) days after the postmark date on the envelope that contained the notice and claim form (see CPLR 5222‑a). By then the bank will likely have finished its 30‑day hold period and may already have turned the money over to the sheriff or marshal. At that point you still have options:

ask the creditor to release the protected funds voluntarily;

file a petition or motion under CPLR 5225(c) or CPLR 5240 asking a judge to direct the return of exempt money (for example, a “Petition to Turn Over Exempt Social Security Benefits” under 5225(c) or a “Motion to Vacate Execution and Refund Exempt Wages” under 5240); or

assert the exemption when the sale proceeds or payout gets distributed.

But using the 20‑day window avoids those extra steps and keeps the funds from leaving the bank in the first place.

Q 7. What role does the garnishee play?

The garnishee is forbidden to release or transfer the asset to anyone except the sheriff (or as a court later orders). If the garnishee violates the restraint, the creditor can sue it for the value of the property.

If you need help, complete this intake form.

Case Study: Vehicle Seizure—Criminal vs. Civil Paths

To see how the levy rules you just read about apply on the street, consider what happens when a creditor targets a debtor’s car. New York actually has two completely different seizure statutes and it is easy to confuse them:

| Scenario | Governing law | Who can seize | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

Criminal – driver caught with a suspended license (aggravated unlicensed operation) | Vehicle & Traffic Law § 511‑c | Police officer | Evidence/forfeiture in the criminal case |

| Civil – creditor wants the car to satisfy a money judgment | CPLR Article 52, mainly §§ 5232 & 5233 | Sheriff, marshal, or Support Collection Unit | Sell car, apply proceeds to judgment |

Below is the civil‑judgment pathway—the one relevant if a court has entered a money judgment against you:

Creditor obtains an execution. The clerk or court issues a writ describing the judgment and authorizing enforcement.

Sheriff levies by service or seizure. Once the sheriff hands the execution to you (or the person holding the car) a lien attaches; if the car is sitting in your driveway, the sheriff may physically tow it away.

Turnover order if you won’t cooperate. If the vehicle is hidden or out of reach, the creditor can petition the court for a § 5225 turnover order compelling you to surrender it. Disobeying can trigger contempt sanctions on top of the car’s eventual sale.

Why this matters: Many debtors see police tow trucks on TV and assume a creditor can do the same thing overnight. In reality, the creditor has to follow the Article 52 steps above—often slower but fully enforceable once the sheriff is involved.

Restraining Notice vs. Levy — and Other “Freeze vs. Seize” Tools (New York Law)

| Device: | What it does: | Who issues it: | Result: Freeze or Seize? | Key statute |

| Restraining Notice | Orders a debtor or third‑party garnishee not to transfer specific property or money. No officer involvement. | Judgment creditor’s attorney (or the court clerk) signs and serves it by mail, hand delivery, or certified email. | Freeze. Creates an immediate restraint for one year (can be extended) but does not remove the property; a turnover proceeding is still required to get the cash or item. | CPLR § 5222 |

Levy by Service of Execution | Sheriff/marshal serves an execution; property in garnishee’s hands is frozen and a lien attaches. | Sheriff, marshal, or SCU on creditor’s written directive. | Freeze (lien) for 90 days unless perfected. | CPLR § 5232 (a) |

| Levy by Seizure | Sheriff/marshal physically removes personal property capable of delivery. | Sheriff, marshal, or SCU. | Seize (custody) pending auction. | CPLR § 5232 (b) |

Income Execution (Stage 1) | Marshal serves employer; first 20 days are a freeze giving debtor a chance to pay voluntarily. | Judgment creditor initiates; marshal serves. | Freeze wages; if debtor doesn’t pay, Stage 2 garnishment begins. | CPLR § 5231 |

| Order of Attachment (pre‑judgment) | Sheriff seizes or restrains defendant’s assets before a money judgment is entered. | Court order on plaintiff’s motion with bond. | Freeze or Seize depending on order. | CPLR Art. 62 |

Receivership Order | Court appoints a receiver to take custody of property (often rents, business assets) to satisfy judgment. | Court after motion. | Seize (custody + management). | CPLR § 5228 |

Bottom line for consumers as to freezes and seizures:

A restraining notice can hit your bank account with nothing more than the creditor’s lawyer’s signature—it freezes funds just as fast as a sheriff’s levy, but it won’t automatically empty the account until the creditor wins a turnover order.

Levy by seizure is the only Article 52 device that lets an officer grab tangible property on the spot. Everything else starts as a paper freeze and turns into a taking only if the creditor follows up in court. : Judgment Debtors’ Obligations (CPLR § 5232)

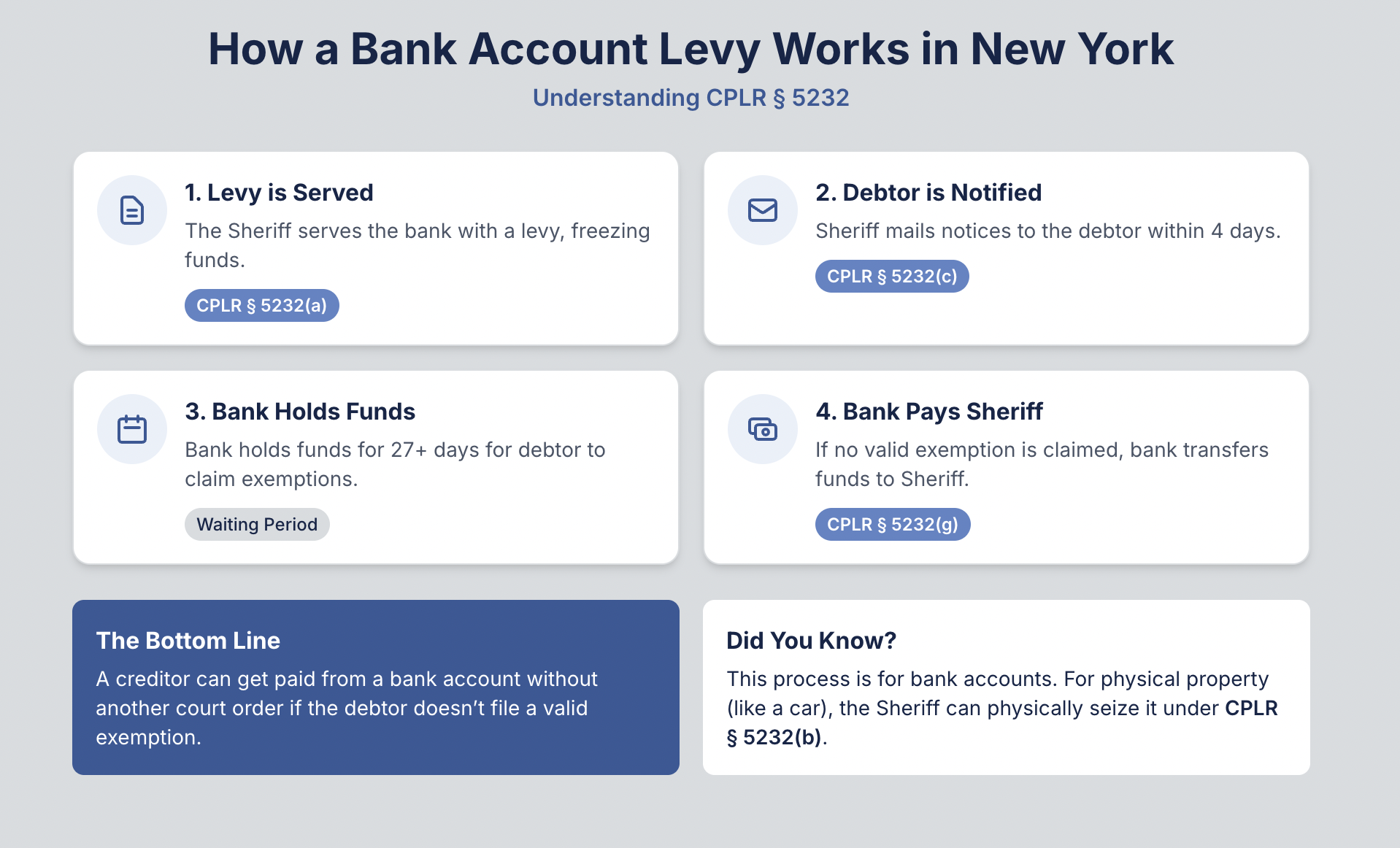

Enforcement Officer (Marshal) May Take Money on 30th Day without a Turnover Order (Court-Ordered Asset Surrender)

Bank accounts:

- A turnover order is usually not required. Once the marshal or sheriff serves an execution under CPLR § 5232 (a), the bank freezes the funds, runs the 27-/30-day Exempt Income Protection Act (EIPA) timetable, and—if no valid exemption claim is received—remits the money to the enforcement officer automatically. The officer then pays the creditor. A turnover order is needed only if the bank refuses, if the 90-day levy window lapses without payment, or if the creditor wants to reach funds the bank is disputing (e.g., a joint account).

“§ 5232(b) seizure” vs. bank levy:

§ 5232 (b) applies to tangible property “capable of delivery” (cash in a safe, jewelry, vehicles), not to bank deposits. So banks never pay under 5232(b).

Notice requirement:

For bank levies: an EIPA notice must go to the debtor within 4 days unless the debtor got one within the past 12 months (CPLR § 5232(c); § 5222-a). The notice travels after the bank is restrained; there is no advance warning.

For physical seizure under § 5232 (b): the marshal gives a copy of the execution to the person from whom the item is taken at the moment of seizure. No prior notice to the debtor is required.

Timing and Notice of Exemptino Claim Form

Bank levies: Once the marshal serves the execution, your account is frozen. After the mandatory 27-/30-day EIPA waiting period—and unless you file a valid exemption claim—the bank will automatically release the money to the marshal without any extra court order.

Seizure rule: The “grab-it-now” power in CPLR § 5232 (b) applies only to physical items like cars or jewelry, never to money sitting in a bank.

Notice timing: You learn about a bank freeze only after it happens (EIPA notice within four days). A physical seizure comes with no advance warning; the officer hands over the paperwork at the moment of taking.

New York Law CPLR 5232

New York Law CPLR 5232

| Point | Statute (law) |

|---|---|

| Bank must remit after 27-/30-day hold | CPLR § 5232(g) – bank “shall … pay to the sheriff” after the hold unless an exemption claim is pending. |

| Levy on a bank account is made by service, not seizure | CPLR § 5232(a) – covers debts and property “not capable of delivery.” |

| Tangible-property seizure authority | CPLR § 5232(b) – sheriff may “take the property into custody.” |

| EIPA notice within 4 days | CPLR § 5232(c) & § 5222-a(b). |

So, in ordinary practice a creditor gets paid from a frozen bank account without going back to court, provided the debtor doesn’t assert a valid exemption and the bank follows § 5232(g).

Conclusion: Turn Knowledge into Leverage

New York’s levy rules boil down to one strategic insight: the first event is almost always a freeze, not a grab. If you recognize that, you gain precious days—or even months—to protect exempt money, negotiate with the creditor, or steer the case back to court on your terms.

Know the countdowns. A bank levy buys you 27–30 days; a service levy buys you 90. Mark those dates the moment a notice lands.

Assert exemptions early and in writing. File the EIPA form within 20 days; raise statutory exemptions (§ 5205) in any turnover or contempt hearing.

Leverage the creditor’s costs. Seizing, storing, and auctioning property is expensive. A realistic payment plan can look better to a creditor than a fire‑sale price after poundage and storage fees.

Use the court when the creditor overreaches. CPLR §§ 5225, 5240, and 5241 let you move to vacate a levy, compel return of exempt funds, or modify an execution that violates the rules.

Stay proactive. Silence helps the creditor; timely objections and documented communications help you.

Bottom line: Freezes can feel final, but they’re really a warning shot. Act within the statutory windows and you can keep essential funds, cut a deal you can live with, or even turn the tables in court.