This blog post provides an introduction to New York law on wage garnishment, specifically "Income executions" under New York CPLR § 5231.

Perhaps you received a Notice of Garnishment from a New York City Marshal or Sheriff threatening a wage garnishment. This post summarizes New York law only.

A wage garnishment, or income execution, is a legal process by which a percentage of your wages is withheld directly from your employer. The calculation of the amount requires some understanding.

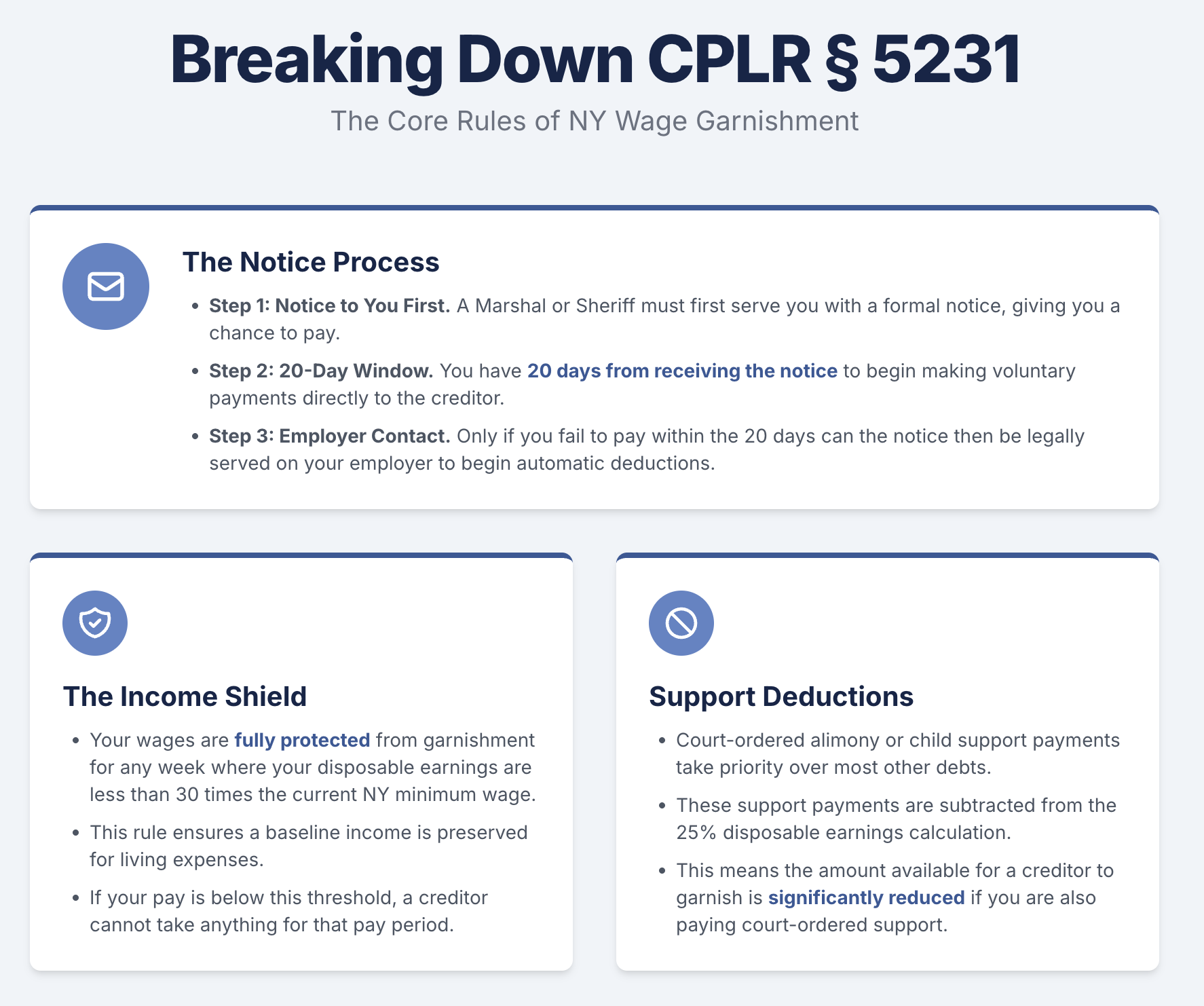

Breaking Down CPLR 5231: Top 5 Wage Garnishment Provisions

- An income execution may initially require voluntary installments of up to 10% of gross weekly income, before employer withholding rules apply, but the amount actually withheld from wages is subject to federal and state limits based on the debtor’s disposable earnings. (N.Y. C.P.L.R. 5231(b)).

- No amount shall be withheld from the debtor's earnings for a week unless their disposable earnings exceed 30 times the federal or state minimum hourly wage, whichever is greater (N.Y. C.P.L.R. 5231(b)(i)).

- The amount withheld from the debtor's earnings per week shall not exceed 25% of their disposable earnings or the amount exceeding 30 times the minimum hourly wage, whichever is less (N.Y. C.P.L.R. 5231(b)(ii)).

- If the debtor's earnings are subject to alimony or support deductions, the withheld amount shall not exceed the amount that 25% of the disposable earnings for the week exceeds the alimony/support deductions (N.Y. C.P.L.R. 5231(b)(iii)).

- The terms "earnings" and "disposable earnings" are defined as compensation for personal services and the part of earnings remaining after legally required deductions, respectively (N.Y. C.P.L.R. 5231(c)).

If you need help, complete this intake form.

Notice Must Be Provided to You First (before it's served on your employer)

When a creditor has been granted court authority for an income execution, the creditor prepares a notice, which specifies:

- The name and address of the person or company from whom the debtor is receiving or will receive income;

- The amount and frequency of the payments;

- The installment amount the creditor is seeking from each payment and

- A notice to the debtor that unless he or she makes these installment payments directly, the notice will be served on the party who owes them income, and they'll be compelled to make the payments instead.

The notice is generally delivered to a sheriff or marshal who serves it on the debtor (in the ways allowed for a summons or by certified mail) in the county where the debtor lives or works, and the debtor has 20 days under current New York law to comply.

If the debtor fails to make those voluntary payments or simply can't be found, then twenty (20) days later, the sheriff or marshal may serve the income source (your employer) with the notice, at the creditor’s request. This is usually done through personal service or certified mail, and there is a specific process for service on state government employers. If the debtor has made some direct payments before defaulting, the amount they have paid and the amount remaining due need to be written onto the notice before it is served on the income source.

New York Caselaw Mandating Notice Provided to the Debtor First

- Under New York law, the initial service of income execution is made on the judgment debtor, thereby offering them a chance to fulfill the payments. This requirement was established in Oystermen's Bank & Trust Co. v. Manning, 298 N.Y.S.2d 355 (Sup 1969).

- Serving the judgment debtor with this notice is a mandatory step before levy against the employer can be made, as outlined in Kaplan v. Supak & Sons Mfg. Co., 260 N.Y.S.2d 374 (N.Y. City Civ. Ct. 1965).

- This rule is applicable even when the judgment debtor resides outside New York, as long as their employer operates within the jurisdiction of New York. This jurisdictional nuance is highlighted in both Oystermen's Bank & Trust Co. v. Manning, 59 298 N.Y.S.2d 355 (Sup 1969) and Kaplan v. Supak & Sons Mfg. Co., 260 N.Y.S.2d 374 (N.Y. City Civ. Ct. 1965).

- For instance, in the case Oystermen's Bank & Trust Co. v. Manning, a creditor aimed to implement an income execution against a debtor's employer located in New York. Despite the debtor now residing in California, they needed to be informed and provided an opportunity to make installment payments before the income execution could be initiated.

If you need help, complete this intake form.

How Much Money Can the Creditor Demand From a Single Paycheck?

It's important to note that an income execution can't seek all or most of the income being paid to the debtor. The formula for determining how much can be demanded is extremely complex. There is mandatory specific language in the statute explaining this, which must be included in the notice when it is served on the debtor. Here are the basic requirements:

- The income can be wages, salary, commissions, bonuses, or any other payment made for personal services, including pension or retirement plan payments.

- No part of a paycheck may be taken unless the worker’s disposable earnings for that week exceed 30 × the greater of the federal or applicable state minimum wage.

- Part One (debtor pays): cap is 10 % of gross weekly income.

Part Two (employer withholds): once served on the employer, the deduction can’t exceed the lower of 25 % of disposable earnings or the amount over the 30‑times‑minimum‑wage floor. - If the debtor is under a court order to pay alimony or child support, the amount of alimony or support must be deducted first before making the determination explained in the paragraph above.

The usual exemptions from satisfaction of a judgment, discussed in other blog posts in this series, still apply.

The Process After Notice Is Served on the Income Source (i.e. employer)

When an income execution has been served on a source of income, the employer must begin withholding the specified amount from their payments to the debtor and turn it over to the sheriff or marshal to be paid to the creditor. If this doesn't happen, the creditor can begin a court proceeding against the income source to recover the accrued installments.

If employment ends, the levy becomes ineffective and the employer must notify the marshal; the execution may be re‑served if the debtor is rehired within 90 days (CPLR 5231[f]). The sheriff or marshal involved with the income execution needs to make any accrued payments and account for their efforts and expenses to the creditor and the court every ninety (90) days.

If there are competing income executions, meaning two or more creditors are seeking to execute on the same income for different debts, then whichever is filed first takes priority. The other may be returned as unsatisfied if there is not enough money left from the debtor's available income to make the payment. However, that creditor could continue attempting to execute the income from future payments until funds are available.

Some Debt Types Permit Wage Garnishment Without a Court Judgment

Creditors can garnish your wages for specific debts without needing a court judgment. These debts include:

- outstanding income taxes,

- court-mandated child support and any back payments, and

- defaulted student loans.

However, for many other debts, such as unpaid credit card bills or medical fees, creditors must first take legal action against you, win the case, and secure a court judgment confirming you owe them money before they're allowed to garnish your wages.

Here is a list of New York City’s Marshals who enforce wage garnishments:

- City Marshal Ronald Moses

- City Marshal Charles Kemp

- City Marshal Gregg E. Bienstock

- City Marshal Martin Bienstock

- City Marshal Henry Daly

If you need help, complete this intake form.