In New York, CPLR § 5205 sets out what personal property is protected from creditors trying to collect a judgment. Below is a practical list of these exemptions, designed to ensure you can meet your basic living needs despite any money judgments against you.

This guide focuses on non-bankruptcy exemptions. While bankruptcy can offer a full fresh start, knowing these protections is crucial—especially if your bank account has been frozen. If you have questions about exempt property, consult an attorney.

If you need help, complete this intake form.

Recent Improvements to New York Exemption Laws (2025)

90% Wage Exemption: 90% of wages earned in the last 60 days from personal services is exempt.

Bank Account Cushion: First $3,425 in an account is protected if it received exempt payments (e.g., Social Security, unemployment, pension) within the last 45 days.

Essential Household Items: Clothing, basic furniture, one fridge, TV, computer, cell phone, cookware, health aids—up to $675 exemption.

Religious Texts & Jewelry: Religious books, family pictures, one wedding ring, plus $1,325 worth of other personal jewelry.

Tools of the Trade: Tools, professional instruments, farm equipment up to $4,075.

Vehicle Equity: Up to $5,500 in one vehicle’s equity, or $10,000 if it’s disability-equipped.

Cash Wildcard: If no homestead is claimed, up to $1,325 in cash or other personal property.

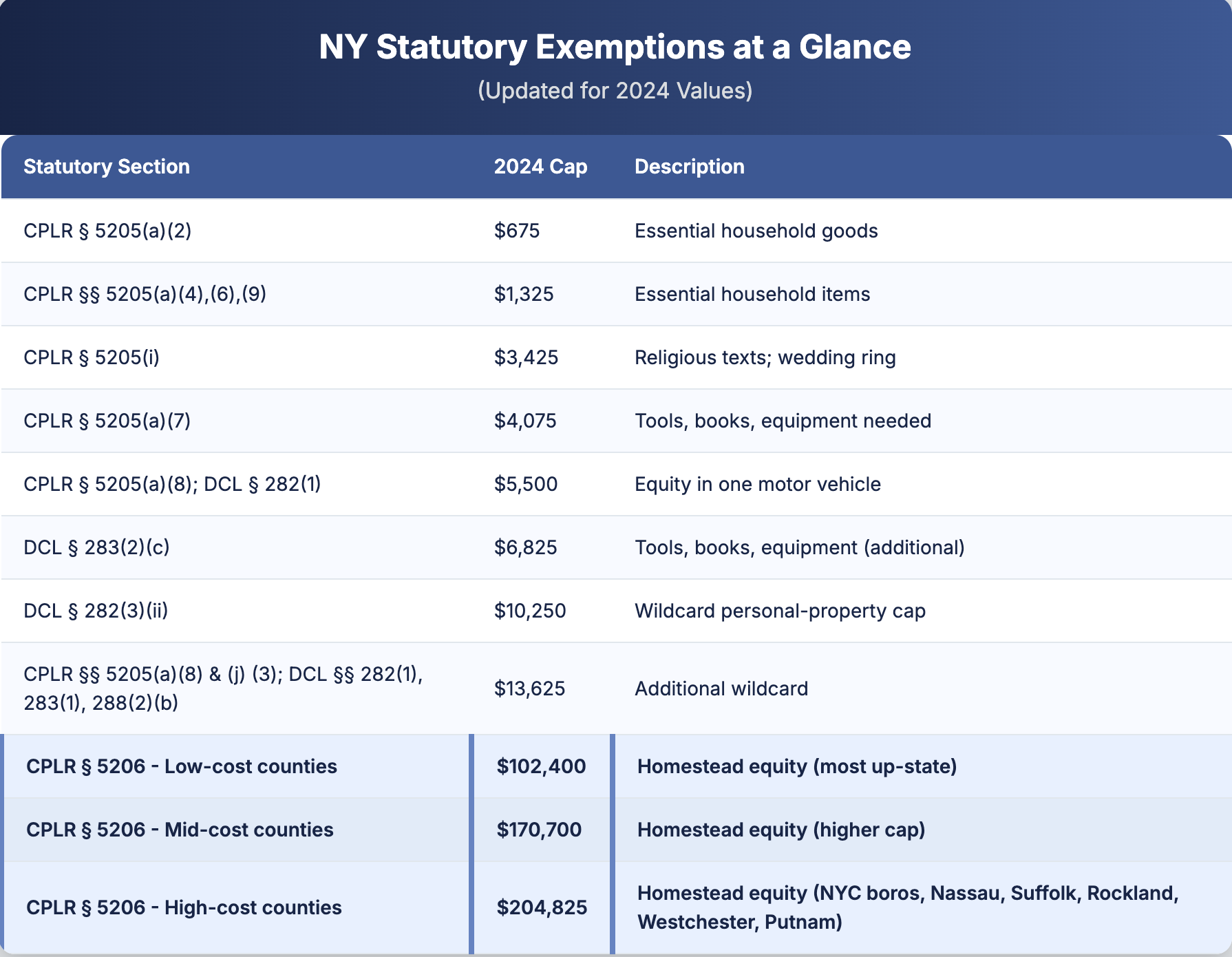

Homestead Equity: Exemption for your primary residence equity, adjusted by county class:

$102,400 in low-cost counties

$170,700 in mid-cost counties

$204,825 in high-cost counties

(Next reset on April 1, 2027.)

These amounts reflect the April 2024 update and remain current through 2025.

Stated Another Way:

| Quick label in table | What it really means | Why it matters (with sources) |

|---|---|---|

| Essential household goods (CPLR § 5205(a)(2)) | Clothing, basic furniture, one refrigerator, TV, computer, cell-phone, cookware, health aids | Lets a debtor keep day-to-day necessities up to $675 in 2024 (dfs.ny.gov, law.justia.com) |

| Religious texts & jewelry / cash wildcard (CPLR § 5205(a)(4),(6),(9)) | Scriptures, one wedding ring, up to $1 k of other jewelry, plus $1,000.00 cash if you don’t claim a homestead | Small sentimental items and a modest “rainy-day” fund are safe (dfs.ny.gov, law.justia.com) |

| Bank-balance cushion (CPLR § 5205(l)) | First $3,425 in an account that received exempt direct-deposit income (Social Security, unemployment, etc.) | Banks may not freeze this (cullenllp.com) |

| Tools-of-the-trade (CPLR § 5205(a)(7)) | Work tools, professional instruments, farm machinery up to $4,075 | Protects the debtor’s ability to earn a living (dfs.ny.gov, law.justia.com) |

| Motor-vehicle equity (CPLR § 5205(a)(8); DCL § 282(1)) | Up to $5,500 equity in one car (or $10 k if disability-equipped) | Keeps essential transportation (dfs.ny.gov) |

Wildcard buckets in bankruptcy (DCL § 283(2)(c) & § 282(3)(iii)) | $6,825 “wildcard” for any personal property plus a separate $10,25 that covers only personal-bodily-injury recoveries | Stacking both in Chapter 7/13 lets a debtor shield $17,075 total, but just the first $6,825 is unrestricted |

| Expanded wildcard / unused-homestead (CPLR § 5205(a)(8)(vehicle) & (j)(3); DCL § 282(1), 283(1),(2)(b)) | $13,625. The rollover wildcard lives in DCL § 283(1) & (2)(b); | Fills gaps when no real-estate equity exists (dfs.ny.gov) |

| Homestead tiers (low / mid / high-cost counties) (CPLR § 5206) | Protects equity in a primary residence: $102,400, $170,700, or $204,825 per owner (doublable for spouses) | Highest shield in the country outside a handful of states (dfs.ny.gov, law.justia.com, thelangelfirm.com) |

Compared to other states' exemption laws, New York is pretty generous in protecting judgment debtor's assets.

A general list of exemptions:

- Income (unless the court deems it unnecessary for reasonable living requirements);

- 90% of wages within the last 60 days (That slice is subject to court reduction if a judge finds it “unnecessary for reasonable living requirements” (CPLR § 5205(d);

- Certain trust income may be protected, but exemptions for annuities, IRAs, custodial accounts, and insurance contracts depend on separate statutory provisions and are not universally covered as “trust income";

- 100% of Maintenance and child support payments awarded by the court;

- Pay and bounty for members of armed forces; and

- Security deposits for rent and utilities.

Statutory list of exemptions:

- social security, including retirement, survivors' and disability benefits;

- supplemental security income or child support payments;

- veterans administration benefits;

- public assistance;

- workers' compensation;

- unemployment insurance;

- public or private pensions;

- Past stimulus payments were exempt while in transit or on deposit (EIPA definition of ‘federal relief’ (Covid-19 Stimulus Relief);

- railroad retirement, and

- black lung benefits.

Personal property exemptions:

- Stoves;

- religious texts;

- family books;

- domestic animals;

- most household goods;

- jewelry (up to $1,000);

- tools ($4,075);

- one vehicle $5,500.00 (or $10,000 disability-equipped)

- $1,325.00 cash if no homestead exemption claimed; trust property of which you are beneficiary (if created by someone else);

- Medical and dental accessions;

- Animals that assist with personal disability;

- Right to accelerate life insurance policy; and

- Certain college tuition savings trust fund monies.

If you're suffering a bank restraint, call us to ascertain your rights. Here's some information about how to combat it.

Click here for New York's Homestead Exemption Law

Case 1: Additional Deposits to Retirement Accounts Within 90 Days of Legal Claim Not Protected from Judgment Creditors

A judgment creditor sought turnover of funds in two retirement accounts (a Traditional IRA and 401(k)) to satisfy a $1.5 million judgment. The court held that deposits made within 90 days before the filing of the lawsuit that resulted in the judgment are not exempt from turnover—regardless of whether they were direct contributions or rollovers from other retirement accounts.

Key Legal Principles:

- Additional deposits to retirement accounts made after 90 days before the interposition of a claim are not exempt from judgment creditors under CPLR § 5205(c)(5)(i)

- The source of additional deposits is irrelevant for exemption purposes under CPLR § 5205(c)(5)(i), except for rollovers from other protected accounts which remain exempt; non-rollover additions made within 90 days before the lawsuit was filed are non-exempt

- Increases in account value, including interest and dividends, retain the same exempt or non-exempt status as their source deposits

Conclusion: When enforcing judgments against retirement accounts in New York, the critical date for determining whether deposits are protected is 90 days before the claim was filed. Deposits after this date are available to creditors, while earlier deposits remain protected. Additions of new, non-exempt funds made within 90 days are reachable; pure rollovers remain protected.

Citation: Matter of Breslin Realty Dev. Corp. v Morgan Stanley, 48 Misc 3d 424 (Sup Ct, Nassau County 2015).

Understanding NY's 90-Day Retirement Account Protection Rule: Balancing Creditor Rights and Retirement Security

The Critical 90-Day Rule Under CPLR 5205(c)(5)

New York law provides robust protection for retirement accounts - but with a crucial limitation. Under CPLR 5205(c)(5), deposits made within 90 days before a legal claim are fair game for creditors. Here's why this matters and how it works.

The Statutory Framework

CPLR 5205(c) creates a comprehensive shield for retirement accounts:

- Protects IRAs, 401(k)s, and other qualified retirement plans

- CPLR 5205(c)(2) treats retirement accounts as if they were spendthrift trusts, for purposes of creditor protection

- Exempts funds from most creditor claims

But paragraph (5) introduces two vital exceptions:

- The 90-day lookback rule

- Voidable transactions under debtor-creditor law

Why the 90-Day Rule Exists: Three Key Purposes

1. Preventing Last-Minute Asset Shielding

- Stops debtors from dumping assets into protected accounts when litigation looms

- Creates a clear temporal boundary for courts to examine

- Mirrors bankruptcy law's preference period concept

2. Balancing Competing Interests

- Protects legitimate retirement savings

- Preserves creditor rights against tactical transfers

- Creates predictable rules for both sides

3. Promoting Transparency

- Encourages regular retirement contributions

- Discourages manipulation of exempt status

- Provides clear guidance for financial planning

Practical Impact for Debtors and Creditors

For Debtors:

- Regular retirement contributions remain protected

- Must plan contributions well before legal issues arise

- Cannot use retirement accounts for last-minute asset protection

For Creditors:

- Clear timeframe for examining transfers

- Automatic non-exempt status for recent deposits

- No need to prove fraudulent intent within 90-day window

The Broader Policy Picture

This rule reflects New York's attempt to balance two crucial policies:

- Protecting retirement security

- Preventing abuse of retirement account protections

Strategic Considerations

- Document timing of retirement contributions

- Maintain regular contribution patterns

- Consider implications for both bankruptcy and non-bankruptcy collection

Conclusion

The 90-day rule serves as a critical checkpoint in New York's retirement account protection scheme. It provides certainty while preventing abuse, creating a workable framework for both debtors and creditors.

Case 2: All IRAs Exempt from Money Judgments Under CPLR 5205(c) Regardless of Funding Source

The court addressed whether an ex-wife could execute a judgment for attorney's fees against her former husband's IRA. After the 1994 amendment to CPLR 5205(c)(2), the court held that all IRAs are exempt from money judgments, regardless of whether they were funded through rollovers from pension plans or established directly by the judgment debtor.

Key Legal Principles:

- CPLR 5205(c)(2)'s 1994 amendment created a blanket exemption for all IRAs from money judgments

- The exemption applies regardless of whether the IRA was created through rollovers or direct contributions

- The relevant date for applying the exemption is when execution is attempted, not when the IRA was created

Conclusion: The 1994 amendment to CPLR 5205(c) established comprehensive protection for all IRAs as retirement savings vehicles, marking a significant change from prior law that only protected rollover IRAs.

Citation: Pauk v Pauk, 232 AD2d 392 (2d Dept 1996).

Case 3: Retirement Account Rollovers Remain Exempt from Attachment Even When Occurring Within 90-Day Period

When a former employee rolled over his exempt employee retirement account to a new IRA account with a nonparty custodian within 90 days of his employer's conversion claims, the court held that the rollover did not constitute a non-exempt "addition" under CPLR 5205(c)(5). The court found no evidence that any additions from non-exempt sources were made to the original retirement account within the 90-day period before the claims were interposed, thus preserving the rollover's exempt status.

Key Legal Principles:

- Retirement assets created as a result of rollovers from other exempt retirement assets are exempt from enforcement of money judgments under CPLR 5205(c)(2).

- A rollover of exempt retirement funds to a new IRA does not constitute a non-exempt "addition" under CPLR 5205(c)(5), even if the rollover occurs within 90 days of a claim.

- Only additions from non-exempt sources (like salary) made within the 90-day period would be subject to attachment.

Conclusion: The exempt status of retirement funds is preserved when transferred between qualified accounts through a rollover, regardless of when the rollover occurs, provided the original funds maintained their exempt status.

Citation: Bayerische Hypo-und Vereinsbank AG v. DeGiorgio, 74 A.D.3d 492 (1st Dep't 2010).

Case 4: Exemption Claim Form Alone Establishes Prima Facie Evidence of Exempt Funds Under CPLR § 5222-a

A judgment creditor moved to challenge a debtor's exemption claim for frozen bank accounts containing allegedly exempt funds. After receiving the debtor's CPLR § 5222-a Exemption Claim Form, the creditor attempted to place additional documentation requirements on the debtor and incorrectly argued that the debtor bore the burden of proving the exemptions. The court rejected these arguments and ordered a hearing.

Key Legal Principles:

- The Exemption Claim Form alone constitutes prima facie evidence that funds are exempt, shifting the burden to the creditor to prove otherwise

- CPLR § 5222-a does not require debtors to provide supporting documentation with their Exemption Claim Form

- The statute requires an actual hearing rather than paper submissions to resolve exemption disputes, particularly to protect pro se debtors

Conclusion: The Exempt Income Protection Act of 2008 created special protections for judgment debtors, particularly those proceeding pro se, by establishing a straightforward exemption claim process that does not require initial documentary proof beyond the claim form itself.

Citation: Midland Funding LLC v. Roberts, 36 Misc. 3d 1232(A) (Sup. Ct. Sullivan County 2012).

I'll explain this legal concept in simple terms and how it relates to exemptions from satisfaction of judgment under NY CPLR 5205.

Marshaling of Assets: Explained Simply

Marshaling of assets is a legal principle that applies when two creditors are trying to collect from the same debtor, but one creditor has access to two sources of payment while the other creditor only has access to one source. The doctrine requires the creditor with access to two sources to collect from the source that the other creditor cannot access, leaving the shared source available for the creditor with limited options.

For example:

- Creditor A can collect from both Property X and Property Y

- Creditor B can only collect from Property Y

- Marshaling would require Creditor A to collect from Property X first, leaving Property Y available for Creditor B

Key Points from the Text

For marshaling to apply, the assets must be tangible property of some kind, though the specific type of property doesn't matter. This includes:

- Mortgaged properties

- Insurance proceeds

- Rents and profits collected

The doctrine can only be invoked when there are two distinct funds or properties available. It doesn't apply if there's only one source of payment.

Relationship to NY CPLR 5205 Exemptions

NY CPLR 5205 provides exemptions that protect certain property from being seized to satisfy judgments. This relates to marshaling in several important ways:

Limited Collection Sources: When certain assets are exempt under CPLR 5205, they cannot be counted as an available "fund" for marshaling purposes. For example, if Property Y contains exempt assets under CPLR 5205, it might not be considered a valid second source for collection.

Priority System: Both marshaling and CPLR 5205 create systems of priority that determine which creditors can access which assets. CPLR 5205 removes certain assets from collection entirely, while marshaling determines the order in which available assets should be accessed.

Protection for Debtors: Both doctrines provide forms of protection - CPLR 5205 directly protects debtors by exempting certain assets, while marshaling can indirectly protect debtors by ensuring more orderly and fair collection practices.

In practical terms, a debtor's attorney would need to consider both the marshaling doctrine and CPLR 5205 exemptions when determining which assets creditors might be able to reach and in what order those assets might be accessed.

Quick Take for Practitioners as to When a Lien Attaches

In New York, a money judgment doesn’t automatically attach to the debtor’s personal property. The lien springs into existence only when you hand the execution to the enforcement officer and that officer actually levies or seizes the property. Until those steps are complete—and the debtor or garnishee gets proper levy notice—your priority is vulnerable:

Competing creditors can race to serve their own executions on different officers.

A Chapter 7 trustee may trump an unperfected lien in bankruptcy.

Levy vs. Seizure: Freezing vs. Taking the Debtor’s Stuff

When judgment creditors talk about “levy” and “seizure,” they’re describing two steps on the same road—but they’re not the same mile-marker.

1. Levy = the legal freeze

Think of a levy as hitting the pause button on the debtor’s property.

What it does: Creates a lien and locks the asset in place, cutting off the debtor’s ability to move or encumber it.

How it happens: The enforcement officer serves the execution (plus any required notices) on whoever holds the property—your bank, employer, tenant, or even the debtor personally.

Scope: Works for tangible goods (e.g., equipment sitting in a warehouse) and intangibles like bank accounts and wages.

Bank accounts: The sheriff’s levy restrains the account—funds are frozen at the balance on the service date.

Wages: An income execution served on the employer levies the paycheck; every pay cycle, a slice is earmarked for you but still sits with the employer or sheriff.

A levy sets your priority date against rival creditors and bankruptcy trustees. Miss it, and someone else may jump ahead of you.

2. Seizure = the physical or constructive grab

Seizure (sometimes called “sale” or “turn-over” in statutes) is the play button—it converts that frozen asset into cash for the judgment.

What it does: Transfers possession or control to the enforcement officer so the property can be sold (tangibles) or paid over (cash, wages).

Trigger events:

Sheriff physically removes inventory or vehicles.

Bank remits the frozen balance after the statutory waiting period.

Employer sends the garnished wages to the sheriff, who then cuts you a check.

Until seizure happens, you have a lien but no money in hand.

Why the distinction matters

Priority battles: Only a timely levy stamps your place in line; seizure alone, if late, can fall to a trustee’s avoiding powers.

Asset mobility: A levy stops the debtor from whisking funds away before you can seize them.

Deadlines & diligence: Courts and sheriffs expect creditors to push the process—inaction after levy can forfeit rights or invite competing claims.

Levy to Cash-Out: A Quick Reference to Article 52 Collection Steps

| Concept | What Article 52 of the CPLR Provides |

|---|---|

| Levy on personal property (CPLR 5232) | A levy occurs when the sheriff (a) physically takes the item or (b) serves the execution and statutory notice on a garnishee (such as a bank, employer, or bailee). The lien attaches the moment that levy is made, and New York treats this act as a constructive seizure—there is no separate statutory step called “seizure.” |

Post-levy conversion to cash (CPLR 5233) | Once the levy is in place, the sheriff converts the property into money: tangible goods are sold at auction, while garnished funds (bank balances, wages) are paid over voluntarily or under a turnover order. |

| Bank accounts | Service of the execution immediately restrains the account balance. After 24 hours, any new deposits are released to the debtor unless a restraining notice under CPLR 5222 is also in effect. Payment to the sheriff follows a brief statutory waiting period (27 days) or, if contested, a court-ordered turnover. |

Wages | An income execution under CPLR 5231 imposes a continuing levy on future earnings. The employer withholds a percentage of each paycheck and forwards the funds until the judgment, interest, and fees are fully satisfied. Priority is determined by the first income execution served on the employer. |

What a Sheriff Can and Can’t Take: Plain-English Map of CPLR § 5232

(a) Levy by service on a third-party (“garnishee”) – Used for property a debtor can’t hand over—bank balances, wages, accounts receivable, crypto keys, etc. The sheriff (or support-collection unit) freezes the asset by serving the execution on whoever holds it. Everything the garnishee owes or will owe during the next 90 days is frozen. The garnishee must keep it frozen and, when due, turn it over to the sheriff and sign needed paperwork. The lien expires after 90 days unless the creditor starts a turnover proceeding. If the creditor targets the wrong person’s property, the creditor is liable for any loss.

(b) Levy by physical seizure – Used for property you can pick up—cars, gear, art. The sheriff takes custody immediately (without disturbing lawful pledgees or lessees) and then serves the same execution on the person who had it.

(c) Notice to the debtor – If the execution itself doesn’t show a notice served within the past year, the sheriff must, within 4 days of hitting any garnishee, mail or personally deliver the execution plus the CPLR 5222(e) consumer notice to every individual debtor. First try the home address; if undeliverable, the workplace; if both unknown, any other known address. The envelope must say “Personal and Confidential” and reveal nothing about a debt.

(d) Who is an “obligor” – An individual (not the judgment debtor) who owes court-ordered child support, spousal support, or maintenance, has been found in default, and has had a chance to contest that default. Retroactive child-support arrears alone don’t make someone an “obligor” for § 5232.

(e) Automatic shields for essential money – Bank accounts that received statutorily exempt benefits (Social Security, VA, unemployment, etc.) in the 45 days before service cannot be restrained below the first $2,500. Separate “minimum-wage floor”: an amount equal to 240 × the higher of the federal or New York hourly minimum wage on the date of levy (e.g., $16.50 × 240 = $3,960 in NYC for 2025; adjusts annually) is immune unless a judge finds it unnecessary for basic living costs. These shields do not block levies for child/spousal support or debts owed to government agencies.

(f) No bank fees on exempt-only accounts – If the levy hits an account that turns out to hold nothing but protected funds, the bank may not charge the debtor any processing fee.

(g) Extra steps for individual bank levies – The sheriff must give the bank an exemption notice plus two claim forms along with the execution. The bank freezes the funds but must hold them for at least 27 days. If no claim arrives by Day 30, the bank may release the money to the sheriff.

(h) Exception for government and support creditors – The special protections in (e), (f), and (g) don’t apply when the creditor is the State of New York (or one of its agencies or municipalities) or when the judgment enforces child support, spousal support, maintenance, or alimony—provided the execution bears a bold legend at the top saying so.

How long does a restraining notice last?

Under CPLR 5222(b) a restraining notice is effective for one year (or until the judgment is satisfied or vacated, whichever comes first). After a year, a fresh notice—or a levy—must be served to keep the restraint alive.

Who serves what—restraining notice vs. levy?

Restraining notice: The judgment creditor’s lawyer can serve it directly (by personal delivery or certified mail) or ask a marshal/sheriff to serve.

Levy (execution): Only a marshal or sheriff can serve an execution and thereby create the lien; lawyers themselves cannot levy.

How quickly can a bank account be frozen and then paid over?

Freeze: Moment the execution is served on the bank—funds on deposit are immediately restrained.

Turnover: Because of the Exempt Income Protection Act, the bank must hold the money at least 27 days while the debtor has a chance to claim exemptions. If no claim is filed, the bank may remit the funds on Day 28–30.

In that sequence, what is the “levy” and what is the “turnover”?

Levy: The service of the execution that freezes the account.

Turnover: The later transfer of the restrained funds to the marshal or sheriff.

When would a creditor’s lawyer choose a restraining notice instead of an immediate levy?

To locate assets before paying marshal fees—e.g., serve a restraining notice on several banks, wait for replies, then levy only where money exists.

To lock down receivables or other intangibles for a full year when speed to cash is less important.

Because the debtor is likely to claim exemptions: a notice freezes funds without starting the 27-day EIPA clock or marshal costs.

When must a levy replace a restraining notice?

Once money is located and the creditor wants payment, an execution (levy) is required; a restraining notice alone never lets the bank or employer hand over funds.