Facing a wage garnishment or bank restraint based on a default judgment? New York law provides multiple, distinct paths to seek vacatur—but the requirements differ materially depending on the statute invoked.

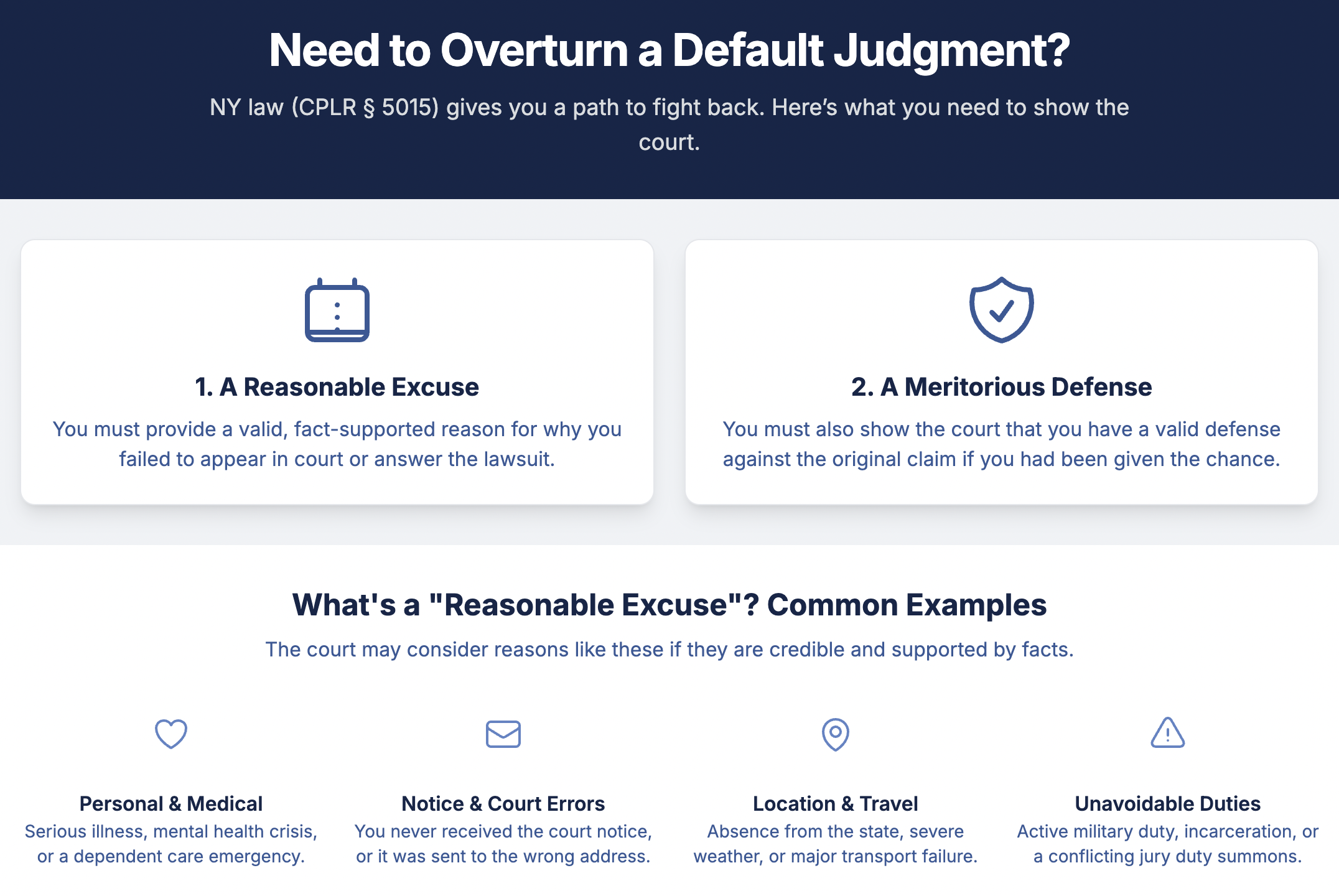

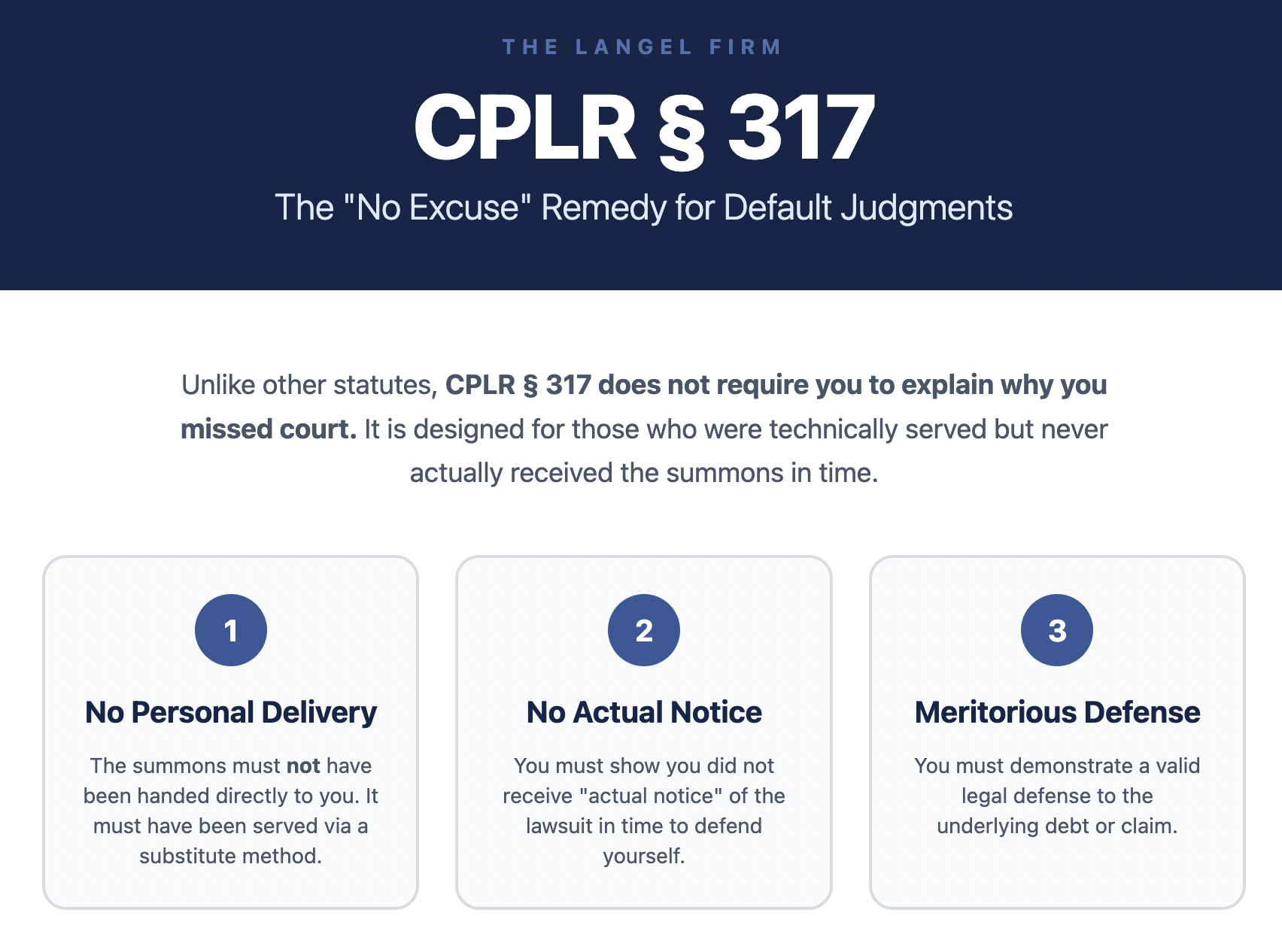

Two provisions are most commonly used: CPLR § 317 and CPLR § 5015. They are often confused, but they operate very differently.

CPLR § 317 applies only where service was not made by personal delivery (for example, “deliver and mail,” affix-and-mail, expedient service, or publication). Under CPLR 317, the defendant does not need to show a reasonable excuse for the default. Instead, the defendant must show (i) lack of actual notice of the summons in time to defend, and (ii) a meritorious defense. Jurisdiction is assumed to be valid.

CPLR § 5015, by contrast, governs broader relief from judgments. When relief is sought based on excusable default under CPLR § 5015(a)(1), the movant must establish both a reasonable excuse for failing to appear and a meritorious defense. However, when vacatur is sought based on lack of personal jurisdiction under CPLR § 5015(a)(4), no reasonable excuse or meritorious defense is required, because a judgment entered without jurisdiction is void.

Understanding which statute applies is critical. Invoking the wrong standard—or overstating the importance of an “excuse” where none is required—can undermine an otherwise strong motion.

A Cautionary Note on “Excuses” Under CPLR 5015

Not every reason for missing a court appearance will support vacatur of a default judgment. Courts applying CPLR 5015 require a credible, fact-specific, and documented excuse, together with a meritorious defense. Ordinary hardship, inconvenience, or routine life obligations—standing alone—are commonly rejected.

The grounds listed below are not guarantees. Their weight depends on contemporaneous proof, internal consistency, and whether the explanation plausibly accounts for the precise default. Any motion should (i) identify the applicable statutory subsection, (ii) explain the default with specificity, and (iii) set forth detailed defenses demonstrating merit.

What's Your Excuse? Potential "Excuses," or Reasons, to Vacate a Judgment:

Lack of personal jurisdiction (improper or defective service under the CPLR, or constitutionally insufficient New York contacts; residence outside New York alone is insufficient).

Serious illness or medical emergency (a sudden condition that objectively prevented participation, supported by medical documentation and directly tied to the missed appearance).

Death or acute medical emergency of an immediate family member (an unforeseen event that reasonably precluded attendance, supported by corroborating proof).

Incarceration or government custody (custody that made physical or remote appearance impossible, supported by official records).

Court or clerk error (administrative mistakes such as misdirected notices, incorrect scheduling, or docketing errors that directly caused the default).

Failure to receive required court notice (non-receipt where service cannot be established or statutory notice requirements were not satisfied).

Improper or misleading service address (service at an address not reasonably calculated to provide notice, absent intentional evasion).

Fraud, misrepresentation, or misconduct by the opposing party (deceptive conduct interfering with notice or participation, pleaded with particularity).

Language access or due-process violations (denial of a requested interpreter or inability to understand proceedings despite reasonable efforts).

Documented mental health crisis (a mental health episode materially impairing the ability to participate at the relevant time).

Active military service or sudden deployment (military obligations conflicting with court appearances where avoidance was not feasible).

Extraordinary, unavoidable work emergencies (truly exceptional obligations beyond the party’s control, supported by employer documentation; routine work conflicts are insufficient).

Remote appearance failures (documented technical failures combined with prompt, good-faith efforts to notify the court).

Severe weather or declared public emergencies (conditions rendering travel or access impossible, supported by objective evidence).

Government-imposed restrictions (mandatory quarantine, isolation, or similar orders directly preventing participation).

The judge has discretion whether to honor or reject your offered excuses. Using any of the above is no guarantee that you'll succeed. Other factors will be considered in your case (for example, time delay, opportunity to defend, strength of defenses, and credibility).

The judge has discretion whether to honor or reject your offered excuses. Using any of the above is no guarantee that you'll succeed. Other factors will be considered in your case (for example, time delay, opportunity to defend, strength of defenses, and credibility).

Using plenty of facts to support your legal position, you would be wise to mount an aggressive challenge. We would be delighted to discuss your case with you. Feel free to complete a short intake form.

Five Key Grounds for Vacating a Judgment under CPLR § 5015

- Excusable Default: Per NY CPLR 5015(a)(1), you can contend that the default occurred due to excusable neglect, meaning you had a justifiable reason for failing to meet the deadline or appear. This requires demonstrating a meritorious defense of the action as well. The excuse must be reasonable under the circumstances, like an unanticipated illness or accident.

- Lack of Jurisdiction: Under NY CPLR 5015(a)(4), you can argue that the court lacked personal jurisdiction over you, which could happen if you were improperly served with the summons and complaint, for instance.

- Newly Discovered Evidence: NY CPLR 5015(a)(2) allows you to assert that new evidence has come to light since the judgment was entered which would likely alter the outcome and couldn't have been discovered in time to request a new trial.

- Fraud, Misrepresentation, or Misconduct: Pursuant to NY CPLR 5015(a)(3), you can claim the judgment was obtained through fraud, misrepresentation, or other misconduct by the opposing party, such as deliberately lying about a crucial fact.

- Reversal, Modification or Vacatur of a Prior Judgment or Order: Under NY CPLR 5015(a)(5), you can contend that a prior judgment or order upon which the current judgment is based has been reversed, vacated, or otherwise modified.

16 Examples of Defenses to Challenge a Default Judgment Under CPLR §§ 5015 and 317

- Complete or Partial Payment: The debt has been entirely or partly paid off, which can be demonstrated through evidence like receipts or financial records.

- Time-Barred Debt: The creditor has exceeded the legal time frame for initiating a debt collection lawsuit, making the action invalid and unenforceable. See statute of limitations.

- Unresolved Dispute: An ongoing disagreement about the debt or contract terms calls into question the legitimacy of the claim.

- Incorrect Service Address: The lawsuit was filed using the wrong contact information, potentially breaching procedural requirements or due process rights.

- Inaccurate Claim Amount: The sum being demanded is incorrect, and records can show the true amount owed is lower or zero.

- Fraudulent Use of Identity: The debt resulted from someone else fraudulently using the defendant's identity, not from the defendant's actions.

- Mistaken Identity: The defendant is mistakenly named as the debtor when the actual debtor is a different person.

- Unapproved Modifications: Alterations to the account or agreement were made without the defendant's awareness or approval, impacting the debt's enforceability.

- Abrupt Account Termination: The creditor or financial institution unexpectedly closed the account without adequate notice or reason.

- Insufficient Dispute Investigation: The creditor failed to properly consider or respond to the defendant's disputes concerning the debt.

- Absence of Legal Standing: The plaintiff lacks a valid legal basis to bring the lawsuit due to the absence of a legitimate agreement or relationship with the defendant.

- Improper or Harassing Collection Tactics: The creditor used strategies that contravene fair debt collection regulations, potentially invalidating the legal action.

- Deceptive Actions by Known Individual or Third Party: The debt arose from fraudulent behavior, including forgery, committed by someone familiar to the defendant or an external party without the defendant's agreement.

- Dishonesty by Creditor or Legal Representative: The creditor or their lawyer engaged in misleading conduct connected to the debt or legal proceedings.

- Minor Party Without Legal "Capacity" to Enter Contract: The defendant was a minor and thus legally incapable of agreeing to the contract that created the debt, rendering it voidable.

- Unrecognized Debt or Previously Settled Obligations: The defendant contests the validity of the debt, indicating that all debts have been previously resolved.

Courts retain discretion in deciding motions to vacate, but that discretion operates within the statutory framework invoked. Under CPLR § 5015(a)(1), judges evaluate the credibility of the asserted excuse alongside the strength of the defenses and the overall equities. Under CPLR § 317, the focus shifts away from “excuses” entirely and centers on non-personal service, lack of actual notice, and the existence of a meritorious defense. Where personal jurisdiction is lacking, vacatur is mandatory under CPLR § 5015(a)(4).

No single factor is dispositive. Courts commonly consider timing, diligence after learning of the judgment, opportunity to defend, prejudice, and credibility. Simply listing reasons for nonappearance—without tying them to the correct statute and supported facts—is rarely sufficient.

A successful motion is built on precision, not volume: identifying the correct statutory vehicle, matching the proof to the legal standard, and presenting concrete, documentary facts. When done properly, even long-standing default judgments can be reopened.

If you are facing enforcement of a default judgment, a prompt and carefully structured challenge may preserve your rights. We would be pleased to review your situation and discuss the most effective strategy under CPLR §§ 317 and 5015.

Stipulation-Based Vacatur Under CPLR 5015(b): Verify Local Practice Before Relying on Clerk Action

Facing a default judgment from a debt collector? Two game-changing New York appellate decisions - Toos and Rodriguez - have established that a properly executed stipulation, once filed with the court, can suffice to vacate the judgment, potentially avoiding a separate motion—subject to the court’s local practice. In Toos, the court explicitly held that a simple stipulation between attorneys under CPLR 2104 is independently binding and enforceable, bypassing the usual requirements of showing excusable default or meritorious defenses under CPLR 5015. The Rodriguez decision further strengthens your position by preventing collectors from imposing artificial deadlines on these agreements. For consumers negotiating with debt collectors, this means you can potentially avoid the cost and complexity of preparing motion papers. A clear stipulation can be an efficient path to vacatur, but the clerk or judge must accept it and may refuse if the language is unclear or circumstances raise concerns. CPLR 5015(b) a clerk may vacate a default judgment upon a filed stipulation, but confirm your court’s local practice—some judges still require a brief motion or order before the judgment is vacated.

- Toos v Leggiadro Intl., Inc., 114 AD3d 559, 980 NYS2d 448 (1st Dept 2014) (reversing denial of motion to vacate default where attorneys had stipulated to vacate under CPLR 2104; holding that CPLR § 5015(b) applies to default judgments entered under CPLR 3215 and permits the clerk to vacate a judgment upon a filed stipulation by the parties. A stipulation between counsel was independently binding and enforceable absent fraud or mistake, particularly given reasonable excuse of lack of notice and strong public policy favoring resolution on merits). Rodriguez v Booth Mem. Med. Ctr., 14 AD3d 688, 789 NYS2d 235 (2d Dept 2005) (enforcing stipulation to restore case to calendar where agreement was clear and unambiguous; holding that when stipulation contains no temporal deadline or other conditions for restoration, court must enforce it according to its terms without resort to extrinsic evidence; rejecting argument that restoration needed to occur by specific date since stipulation contained no such limitation).