In New York judgment enforcement, a "final" order is rarely the end of the story. CPLR § 5015 is one of the principal statutory mechanisms for post-judgment relief in New York, allowing debtors and tenants to seek vacatur of judgments and orders. However, as reflected in recent Supplementary Practice Commentaries by Hon. Mark C. Dillon, this procedural path is strictly governed by statutory mandates.

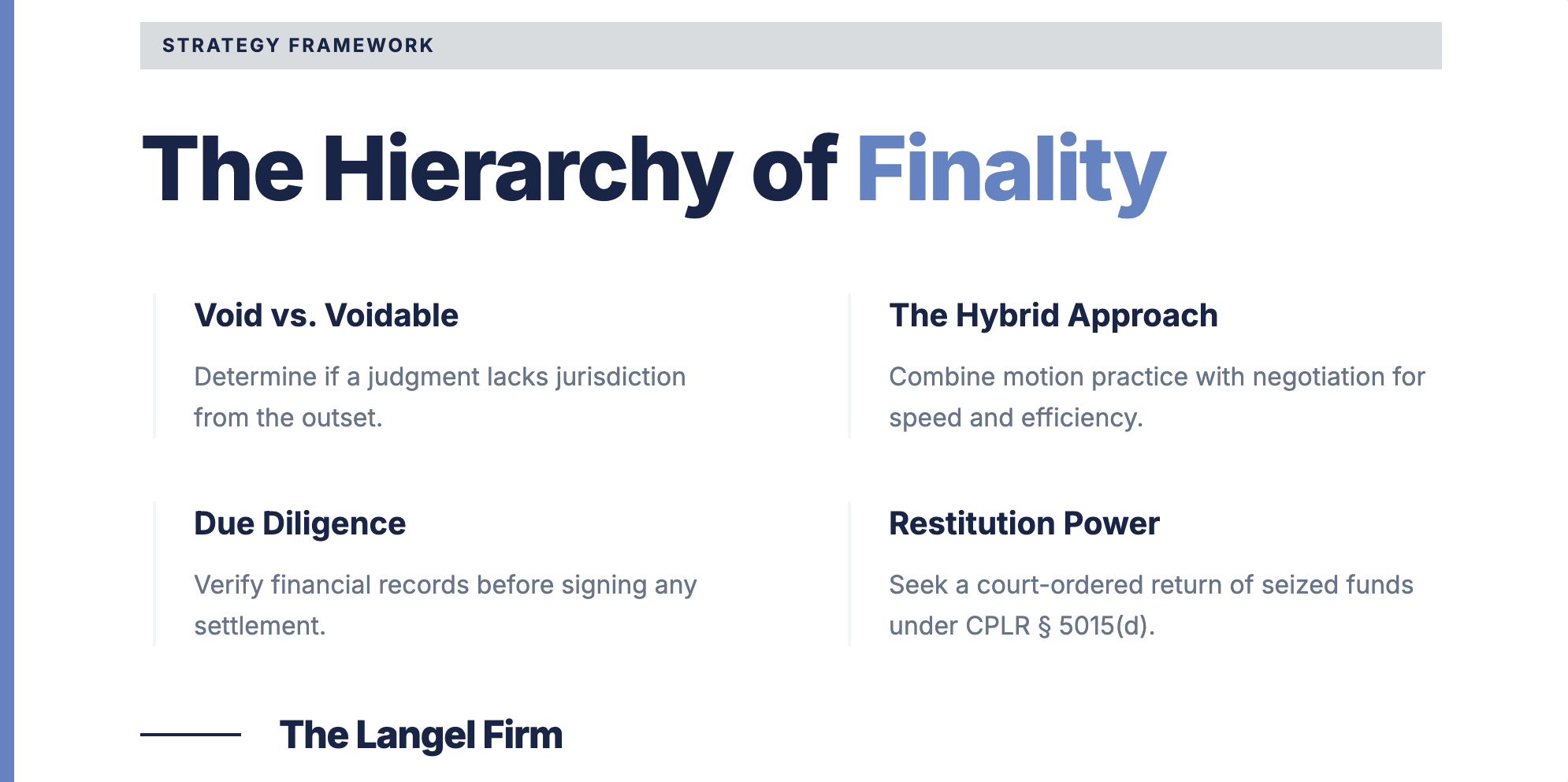

Understanding what may be described as a practical "hierarchy of finality" in New York practice is essential for any judgment debtor. In New York, some judgments are "void" from inception, while others are merely "voidable." The procedural vehicle selected—whether contested motion practice or a negotiated stipulation—can materially affect the likelihood, cost, and timing of relief.

What Does the Law Actually Say About Vacating a Judgment?

To understand your rights, you must first look at the language of the statute itself. CPLR § 5015 provides the specific grounds upon which a court may relieve a party from a judgment:

(a) On motion. The court which rendered a judgment or order may relieve a party from it upon such terms as may be just... upon the ground of:

excusable default...

newly-discovered evidence...

fraud, misrepresentation, or other misconduct of an adverse party;

lack of jurisdiction to render the judgment or order; or

reversal, modification or vacatur of a prior judgment or order upon which it is based.

(b) On stipulation. The clerk of the court may vacate a default judgment entered pursuant to section 3215 upon the filing with him of a stipulation of consent to such vacatur by the parties personally or by their attorneys.

This statutory framework generally permits two mechanisms: a motion under subdivision (a) on specified grounds, or, in the case of certain default judgments under CPLR § 3215, a clerk-entered vacatur upon stipulation under subdivision (b). While CPLR § 5015 is a primary tool, relief may also be available through other paths, such as CPLR § 317 (where a defendant was not personally served and did not receive actual notice in time to defend).

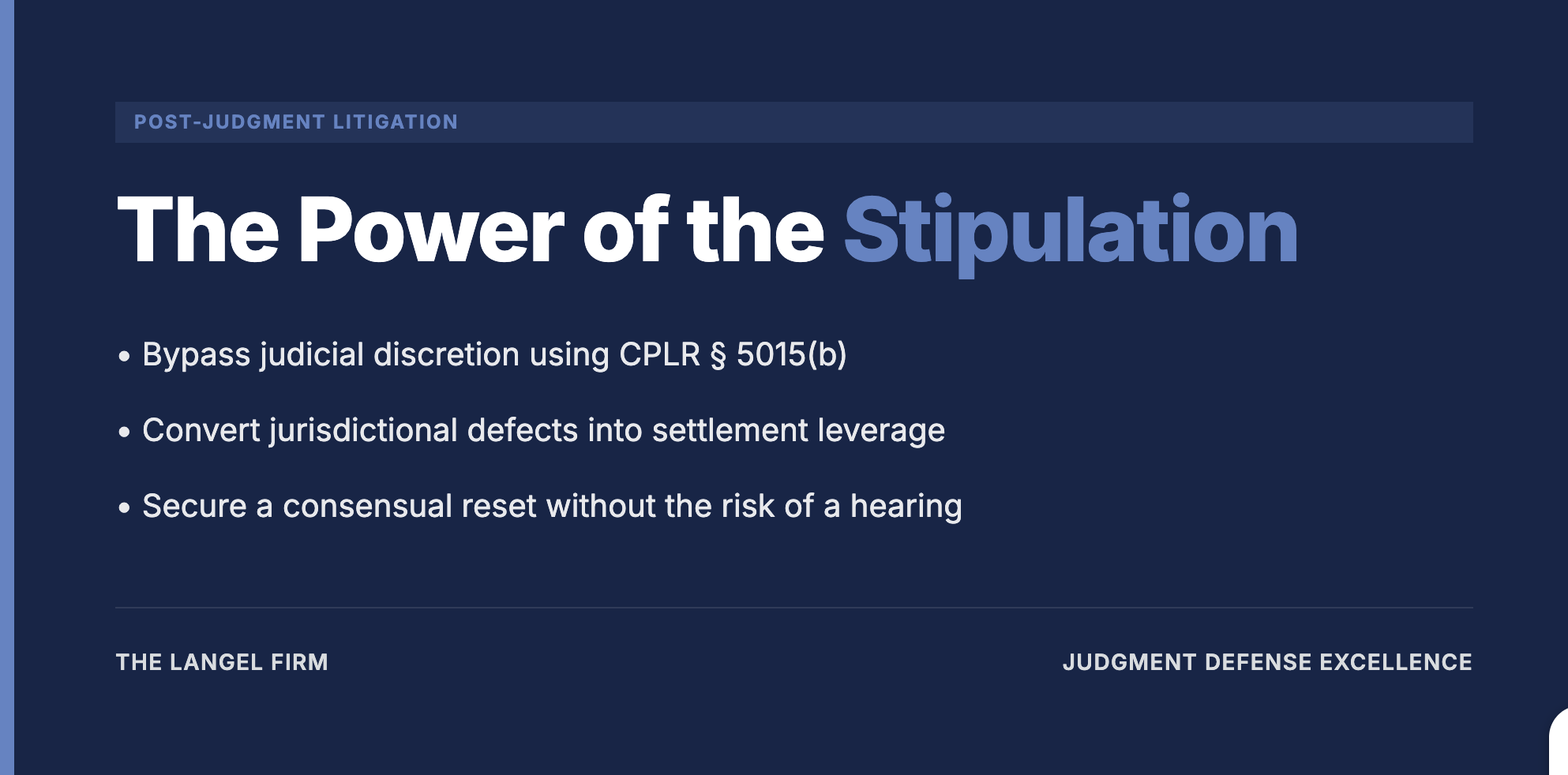

If the Other Side and I Stipulate to Vacate the Judgment, Does Everyone Have to Follow That?

Unlike adversarial motions, CPLR § 5015(b) allows a clerk to vacate a default judgment purely upon a written stipulation of consent between the parties. This pathway is uniquely powerful because, unlike an excusable default under CPLR § 5015(a)(1), a stipulation is not bound by a strict one-year time limit.

This efficiency was highlighted in Studin v. Allstate Insurance Co., 152 Misc. 2d 221 (1991), where the court recognized that written consent between counsel, properly filed, may satisfy the stipulation requirement. By utilizing this section, parties can avoid the need for a judge to adjudicate "reasonable excuses" and move directly back to the merits of the case.

However, the "Hierarchy of Finality" imposes a major limit: third parties are not bound by stipulations to which they were not a party. While the parties to a lawsuit can agree to reset their own procedural clock, they cannot use a stipulation to void a deed already delivered to a purchaser who relied on the regularity of the court's prior judgment. As established in Roosevelt Hardware v. Green, 72 A.D.2d 261 (2d Dept. 1980), a consensual stipulation is a private contract; it cannot disturb the vested rights of a stranger to the litigation, such as a third-party purchaser at a judicial sale.

The Adverse Party Engaged in Misconduct—Can I Use That to Secure a Stipulation?

The relationship between CPLR § 5015(a)(3) (misconduct) and CPLR § 5015(b) (stipulation) is one of leverage. In court, allegations of "intrinsic fraud" (misrepresentations regarding the underlying debt) do not bypass the two-prong requirement of demonstrating both a reasonable excuse for the default and a potentially meritorious defense. As seen in 979 Second Avenue LLC v. Chao, 227 A.D.3d 436 (1st Dept. 2024), if a debtor cannot provide a valid excuse for the initial default, the court may refuse to even hear the evidence of the creditor's fraud.

This procedural barrier is precisely why (a)(3) misconduct serves as such a potent driver for a (b) stipulation. A creditor who realizes the debtor has uncovered material misrepresentations may prefer to resolve the issue via a consensual stipulation rather than risk a public judicial finding of misconduct—even if they believe the debtor lacks a "reasonable excuse." By stipulating under CPLR § 5015(b), the parties reset the case by consent, effectively "curing" the default without the risk of a judge strictly enforcing the two-prong barrier or issuing a scathing order regarding the creditor’s conduct.

The Matrimonial Exception: Notably, the "two-prong" rule is not applied with equal rigor in matrimonial actions. In Adams v. Adams, 255 A.D.2d 535 (2d Dept. 1998), the court explained that the State’s interest in the "marital res" favors a more liberal approach. In Adams, the court vacated a financial default despite a "questionable" excuse because there was an arguably meritorious defense. However, in commercial matters, the (b) stipulation remains the safer and more certain path to vacatur.

I Never Got Sued—Can a Stipulation Help Me Get My House Back After a Sale?

A challenge under CPLR § 5015(a)(4) is a powerful tool because it may render the judgment void for lack of jurisdiction, subject to proof and procedural posture. Unlike discretionary grounds, a proven jurisdictional defect can, in appropriate circumstances, invalidate even a completed enforcement sale.

As seen in Roosevelt Hardware, while a stipulation under CPLR § 5015(b) cannot nullify a consummated sale, a judicial determination of lack of jurisdiction is typically required to disturb title held by a non-party purchaser. Strategically, if a debtor has a strong "lack of service" argument, the creditor may prefer to stipulate to vacate the judgment and allow the debtor to answer rather than risk a traverse hearing that could void the entire enforcement history and destabilize third-party reliance interests.

We Already Settled Out of Court—Is That Agreement Final if it Breaks the Law?

Stipulations and consent judgments remain subject to overriding statutory and public policy constraints. In 390 West End Associates v. Baron, 274 A.D.2d 330 (1st Dept. 2000), the parties entered a consent judgment to deregulate a rent-stabilized apartment. The court vacated the judgment years later, holding that an agreement to waive statutory benefits is void as against public policy. Generally, a settlement is not final where the agreement violates non-waivable statutory protections or public policy.

I Just Found Proof That the Debt Was Paid—Is It Too Late to Change the Outcome?

The prospect of a viable motion under subdivision (a)(2) (newly-discovered evidence) often leads to a negotiated resolution. While this motion must be brought within a "reasonable time," it provides the evidentiary weight necessary to encourage a creditor to settle. This requires a showing that the evidence could not have been discovered earlier with due diligence and would likely have produced a different result. In Mulhern v. Touro College, 226 A.D.3d 788 (2d Dept. 2024), the court clarified that once a final judgment is entered, CPLR § 5015(a)(2) is the appropriate vehicle rather than a motion for renewal.

If I Win My Case, Do I Get My Seized Money Back?

If a judgment is set aside after money has already been seized or paid—whether by court order or stipulation—the court may, in its discretion, order restitution where equity and good conscience require. Under CPLR § 5015(d), the court may direct and enforce restitution in a manner similar to an appellate reversal. In Hamway v. Sutton, 237 A.D.3d 92 (1st Dept. 2025), the court emphasized that restitution is an equitable tool intended to restore the parties to their original positions when a judgment is vacated.

Strategic Lessons for Judgment Debtors

The Efficiency of the "Hybrid" Approach: An effective technique for resolving a default is to bring a formal motion to vacate by Order to Show Cause while simultaneously negotiating a stipulation to vacate. The pending motion creates the necessary pressure for the creditor to settle, while the resulting stipulation provides a more efficient resolution that avoids the uncertainty of a discretionary ruling on the "reasonable excuse" prong.

Don't Sign Until You've Checked the Financial Records: In Van Ostrand v. Latham, 222 A.D.3d 1382 (4th Dept. 2023), the court refused to set aside a settlement because the plaintiff had access to the financial records before signing. Due diligence requires a specific search for original contracts and ledgers, proof of assignment, and mailing logs (to verify additional notice under CPLR § 3215(g)). If you stipulate to a judgment or vacatur while these records are in your possession, New York courts will generally not rescue you from a lack of diligence.

The Order to Show Cause (OSC): Motions under CPLR § 5015(a) are often brought by Order to Show Cause, particularly where a stay is sought, though in some circumstances a notice of motion may suffice depending on local court rules and the relief requested. The OSC allows the court to structure service and, where appropriate, issue interim relief such as a Temporary Restraining Order (TRO) to stay bank levies or evictions while the motion is pending.

Attorneys' Fees as Leverage for a Deal: In Wolf Haldenstein Adler Freeman & Herz LLP v. 270 Madison Avenue Associates LLC, 211 A.D.3d 501 (1st Dept. 2022), the court affirmed that a prevailing tenant can recover attorneys' fees even if the landlord is granted minor offsets. If a debtor has a meritorious path to "prevailing party" status, creditor exposure may materially increase. This financial risk often leads the parties to settle via a CPLR § 5015(b) stipulation to mitigate mutual risk.

At The Langel Firm, we analyze every judgment through this procedural hierarchy. A rigorous procedural defense is often essential to protecting client interests in post-judgment enforcement proceedings.

Educational analysis only. Not individualized legal advice.