In New York practice, while retirement accounts and support payments are strongly protected under CPLR Article 52, those protections are subject to important statutory exceptions—particularly in the context of support enforcement.

The cases discussed below are doctrinally significant because they establish the specific thresholds at which a debtor’s exempt status yields to a creditor’s right to recovery. For debtors and their principals, understanding these boundaries—and the strategic theories used to navigate them—is essential to maintaining an effective litigation posture and protecting liquidity.

Can a Creditor Reach Your Retirement Account to Collect Support Arrears?

Under CPLR § 5205(c), individual retirement accounts (IRAs) and 401(k)s are generally shielded from the reach of judgment creditors. However, CPLR § 5205(c)(4) carves out a significant exception permitting enforcement against retirement funds to satisfy orders for support, alimony, or maintenance.

As established in Berger–Carniol v. Carniol, 273 A.D.2d 427 (2d Dept. 2000), the court may authorize execution against otherwise exempt retirement funds to satisfy support arrears. The Second Department has recognized that certain matrimonial counsel fee awards may be treated as support for enforcement purposes. Furthermore, the contribution protections under CPLR § 5205(c)(5) generally do not insulate retirement funds from the enforcement of support arrears, making these accounts uniquely vulnerable in the matrimonial context.

When Does a Debt Threaten Your Professional License Under DRL § 244–c?

Judgment enforcement in New York extends beyond seizing bank accounts; it can target a debtor’s very livelihood. Under DRL § 244–c, the four-month arrearage threshold authorizes the court to direct the commencement of license suspension proceedings through the appropriate licensing authority.

Because professional licensure is often essential to income generation, license suspension proceedings can significantly affect settlement dynamics. As illustrated in Berger–Carniol v. Carniol, 273 A.D.2d 427 (2d Dept. 2000), this mechanism is particularly potent for professionals such as lawyers, mortgage brokers, and real estate brokers. The court reinforced that the four-month threshold serves as a trigger for initiating disciplinary proceedings, forcing a resolution in cases where a mere money judgment might otherwise remain unsatisfied.

When Does a Bank’s Right of Setoff Outrank Your Judgment Creditors?

In New York judgment enforcement, success is determined by substantive priority hierarchies. Setoff rights under DCL § 151 generally arise where mutual debts exist and certain enforcement events—such as a restraint or bankruptcy filing—affect the depositor.

In Kates v. Marine Midland Bank, N.A., 143 Misc. 2d 721 (Sup. Ct. 1989), the court clarified that if a bank’s right of setoff was mature prior to the service of a restraining notice, it may take priority over a later-served judgment creditor. Similarly, Godfrey-Keeler Co., Inc. v. Regent Laundry & Dry Cleaning Corp., 9 N.Y.S.2d 309 (Sup. Ct. 1939) established that where mutual debts exist and the right of setoff is mature prior to a levy, a garnishee may assert priority over subsequent enforcement restraints.

Does the Setoff Apply to Future or Speculative Debts?

While DCL § 151 allows the setoff of unmatured debts—those certain to become due—it does not extend to purely contingent liabilities. As seen in Trojan Hardware Co. v. Bonacquisti Const. Corp., 141 A.D.2d 278 (3d Dept. 1988), if an obligation is purely speculative, it is ineligible for setoff. This distinction is a primary battleground in collection defense; if a bank sweeps an account based on a speculative liability, the setoff may be legally void, providing an opening for the debtor to recover the seized funds.

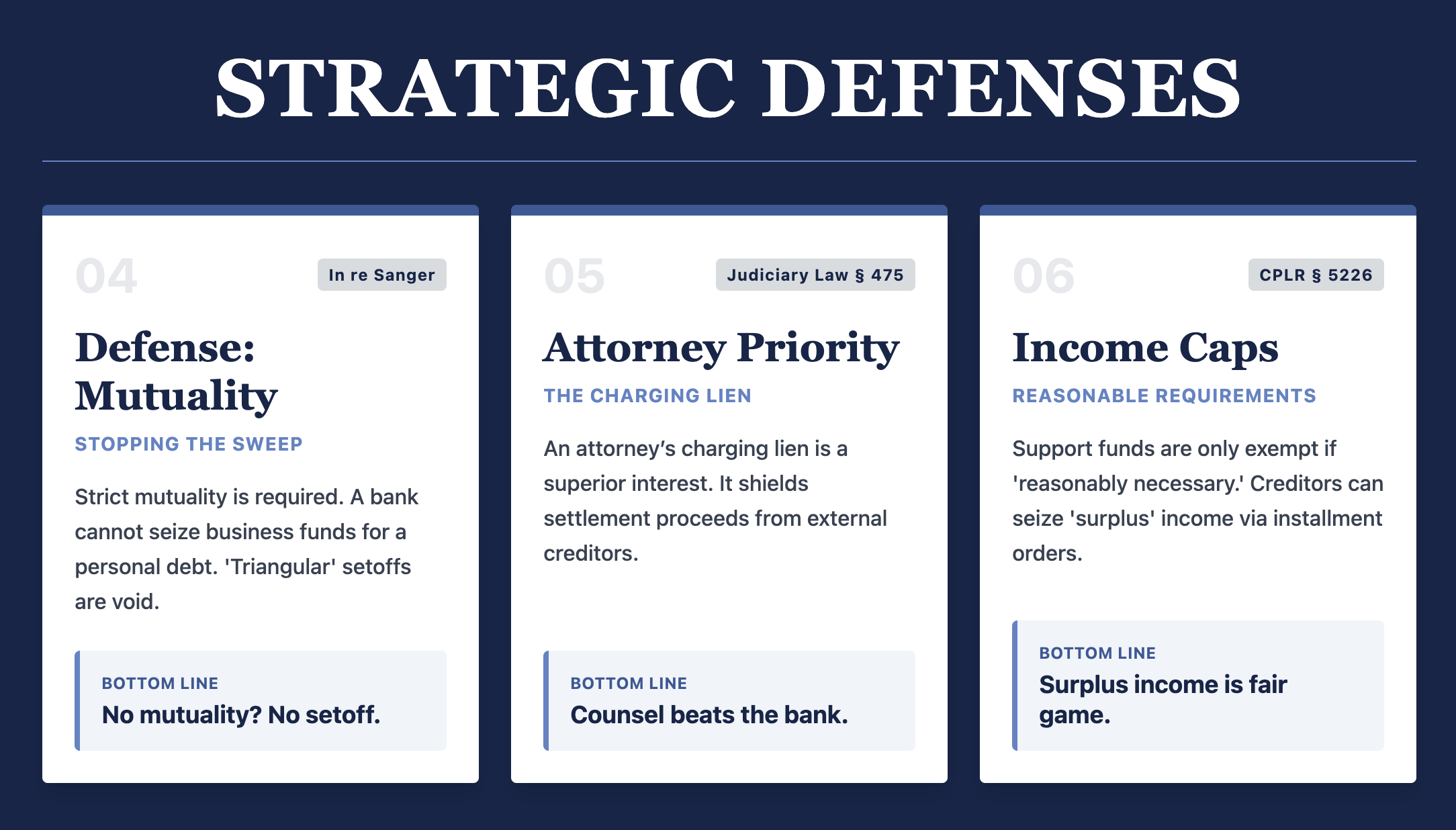

Can a Bank Seize Your Business Funds for a Personal Debt?

A valid setoff requires strict mutuality: the debts must be between the same two parties in the same legal capacity. The case of In re Sanger, 45 Misc. 3d 941 (Surr. Ct. 2014) warns against "triangular" setoffs. In that matter, the court rejected a bank's attempt to seize funds from a law firm's account to satisfy debts owed by an estate, holding that a bank-depositor relationship is grounded in contract and cannot be manufactured by linking separate relationships to reach a third party's funds.

Does an Attorney’s Fee Take Priority Over a Bank’s Setoff?

An attorney’s charging lien under Judiciary Law § 475 generally attaches from the commencement of the action and may take priority over later-arising claims. In Lopez v. City of New York, 152 Misc. 2d 817 (Sup. Ct. 1991), the court ruled that an attorney's charging lien was superior to a municipal attempt to set off settlement proceeds against unpaid fines. Priority disputes often turn on the timing of attachment and compliance with CPLR § 5232, but the charging lien remains a powerful property interest that shields proceeds from a client's external creditors.

Can a Judgment Creditor Still Reach "Exempt" Support Payments Through an Installment Order?

The multi-year litigation in Piccarreto v. Mura establishes how creditors can navigate the "reasonable requirements" hurdle. In the 2013 decision (Piccarreto v. Mura, 41 Misc. 3d 295 [Sup. Ct. 2013]), the court ruled that support funds are generally exempt under CPLR § 5205(d)(3) only to the extent reasonably necessary for the support of the debtor and dependents. A creditor may reach the "surplus" via a CPLR § 5226 installment payment order.

However, for transfers occurring before April 4, 2020, former DCL §§ 273–276 applied to transfers made with actual intent to hinder, delay, or defraud creditors. In the 2016 decision (Piccarreto v. Mura, Sup. Ct., Monroe County, June 6, 2016), the court vacated a spousal property transfer as a fraudulent conveyance. For more recent transfers, New York has adopted the Uniform Voidable Transactions Act (DCL Article 10), which continues to allow courts to set aside transfers that lack fair consideration or involve "badges of fraud."

Strategic Lessons for Protecting Your Assets

The following lessons summarize the educational analysis of New York’s enforcement hierarchies:

Maturity and Timing in Setoff: Where mutual debts exist and the right of setoff is mature prior to a levy, a garnishee may successfully assert priority over external creditors.

The Importance of Mutuality: Identifying a lack of mutuality (e.g., personal vs. corporate accounts) remains one of the fastest ways to challenge improper bank account sweeps.

The Charging Lien as a Property Interest: Under Judiciary Law § 475, an attorney’s superior property interest ensures that settlement proceeds are shielded from later-arising claims.

Challenging Procedural "Self-Help": As established in Lopez v. City of New York, 152 Misc. 2d 817 (Sup. Ct. 1991), all creditors must adhere to the strict procedural requirements of CPLR Article 52.

At The Langel Firm, we emphasize that every enforcement tool has a countermeasure. Whether asserting a garnishee's set-off right or litigating the "reasonable requirements" of a household, a rigorous procedural defense is the only way to protect clients' interests.

This article is provided for general informational purposes and does not constitute legal advice. Application of these principles depends on specific facts, timing, and individual case considerations.

This article is provided for general informational purposes and does not constitute legal advice. Application of these principles depends on specific facts, timing, and individual case considerations.